Neurotrophic factors are a family of proteins that are responsible for the growth and survival of nerve cells during development, and for the maintenance of adult nerve cells. Animal studies and test tube (in vitro) models have shown that certain neurotrophic factors are capable of making damaged nerve cells regenerate. Because of this capability, these factors represent exciting possibilities for reversing a number of devastating brain disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Lou Gehrig’s disease, and Huntington’s Disease (HD). (For more information on how HD relates to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, click here.) Currently, scientists are looking for ways to harness neurotrophic factors and somehow induce the damaged nerve cells to regenerate in order to improve the symptoms of people with neurological disorders.

One neurotrophic factor that is particularly relevant to HD is Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF levels are decreased in the brains of HD patients, which might be partly responsible for the degenerative processes of HD. Researchers have recently discovered a link between BDNF, mutant huntingtin, and excitotoxicity, a process by which brain cells die after stimulation. The mutant huntingtin protein invariably leads to the death of nerve cells in the striatum, the region of the brain needed for movements; however, how mutant huntingtin does this damage is unclear. One possibility is that mutant huntingtin lowers levels of BDNF, making nerve cells more susceptible to injury and death. Therefore, therapeutic approaches aimed at increasing BDNF production may be able to counteract the effects of mutant huntingtin and prevent a significant amount of the neurodegeneration that would otherwise occur in HD. (For more information on huntingtin protein, click here.)

What role does BDNF play in HD pathology?^

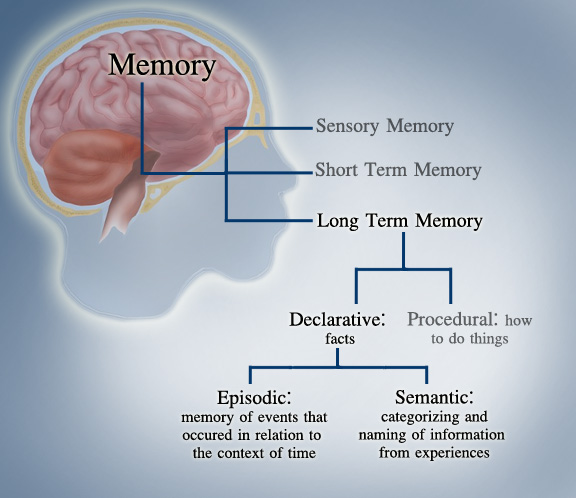

BDNF has been shown to play a role in neuroplasticity, which allows nerve cells in the brain to compensate for injury and new situations or changes in the environment. (For more information on neuroplasticity, click here.) The central nervous system (CNS) has a greater ability to recover from insult or injury than scientists had previously thought. For decades, the prevailing view was that the brain stopped developing after the first few years of life. Connections between the brain’s nerve cells could only be formed during a critical period early in life. After this critical period, it was thought that the brain was unable to form new connections. Thus, if a particular area of the adult brain was damaged or injured, nerve cells would not be able to regenerate, and the functions controlled by that area would be lost forever. However, new research suggests that this view is not entirely correct. Researchers now recognize that the brain continues to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. Neurotrophic factors, such as BDNF, promote the survival and aid in the regeneration of adult neurons.

As mentioned above, the mutant huntingtin protein is harmful to striatal nerve cells in the brain. It also decreases transcription of BDNF, which results in a decrease in BDNF production in people who have HD. Nerve cells require BDNF to survive, but also to regenerate. Less BDNF means less neuroplasticity so the striatal nerve cells are less capable of compensating for injuries. By lowering levels of BDNF in the brain, mutant huntingtin acts as a devastating double-edged sword. First, nerve cells die because there isn’t enough BDNF to effectively combat neurodegeneration. Second, nerve cells are not able to regenerate because there still isn’t enough BDNF. It, therefore, appears that BDNF plays a crucial role in the degenerative process of HD.

How does BDNF work?^

In the brain, BDNF is released by either a nerve cell or a support cell, such as an astrocyte, and then binds to a receptor on a nearby nerve cell. (For more information on HD neurobiology, click here.) This binding results in the production of a signal which can be transported to the nucleus of the receiving nerve cell. There, it prompts the increased production of proteins associated with nerve cell survival and function.

Can exercising promote BDNF production?^

Scientists are increasingly recognizing the capacity of physical activity to maintain and compensate for the deterioration of nerve cell function. Numerous animal studies have reported that voluntary exercise leads to increased BDNF production. In rats, several days of voluntary wheel-running increased levels of BDNF in the hippocampus. This finding is surprising considering that the hippocampus is a structure normally associated with higher cognitive functions such as emotion and memory rather than motor activity. The changes in BDNF levels were found in nerve cells within days in both male and female rats and were sustained even several weeks after exercise.

Similarly, scientists studying HD in mouse models found that HD mice given the opportunity to exercise expressed more BDNF in the striatum than HD mice that didn’t exercise. This is notable because people with HD have particularly low levels of BDNF in the striatum, which is thought to be part of the reason that the striatum is the main site of neurodegeneration in people with HD. Furthermore, motor and cognitive symptoms set in later for HD mice that ran.

In order for exercise to be used as a therapeutic strategy, the type and duration of exercise would need to be determined and probably individualized to each patient. There is debate over what intensity of exercise is best to promote brain health. Although previous reports showed that only rigorous exercise, like treadmill running, stimulated BDNF expression, researchers have more recently found that even a light exercise routine may be sufficient. The downside of high intensity is that sometimes this kind of exercise can be a stressful experience that increases the release of stress hormones, thereby canceling the BDNF-promoting effects of exercise. Also, many individuals are simply unable to perform rigorous exercise. These new reports are very encouraging because they indicate that everyone can enjoy the benefits of exercise by simply engaging in light activities such as walking or doing yard work. (For more information on exercise and HD, click here).

Can BDNF be used to treat HD?^

The discovery of the relation between huntingtin and BDNF is a major step in the path to finding a treatment for HD. Previously, it was thought that mutant huntingtin gained a new function that caused neurodegeneration in the brain. However, researchers now know that HD is caused, not only by this toxic gain of function of mutant huntingtin, but also by a loss of function of normal huntingtin. Normal huntingtin allows BDNF production and plays a role in moving BDNF to the places it is needed most. In the absence of normal huntingtin, BDNF production drops drastically. This realization is a major step toward HD treatment because it indicates that therapeutics need to be aimed not only at preventing mutant huntingtin toxicity, but also at restoring normal huntingtin function.

A simple way to restore the loss of normal huntingtin function in the case of decreased BDNF production would be to administer BDNF itself. However, when BDNF is taken by routes common for other drugs, such as orally or injections into the body, it can’t reach the brain where it is needed; there is a barrier – the blood-brain barrier – that makes it difficult for substances to pass between the body and the brain. So numerous laboratories are currently trying to develop ways to deliver BDNF to the brain. However, there are still several steps that need to be taken before a drug can be developed based on this research. Scientists need to understand exactly how huntingtin “communicates” to the BDNF gene to increase its activity. Trials are already under development to deliver BDNF via gene therapy to HD transgenic mice and researchers are confident that research in this area will progress rapidly.

Research on BDNF Inducers^

While BDNF itself is not yet a viable treatment for HD, scientists are actively researching BDNF inducers, which are drugs that increase levels of BDNF in the brain.

Citalopram (Celexa)^

Citalopram is an anti-depressant that is currently on the market to treat people with depression, and goes by the brand-name Celexa. Citalopram is a particular type of anti-depressant called a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). This class of anti-depressants are believed to raise BDNF levels; SSRIs cause an increase in serotonin levels, which causes nerve cells to make more BDNF. Therefore, SSRIs are being investigated for their potential ability to slow the progression of HD – as described in more detail here.

Scientists investigated how citalopram might help people with HD in a phase II clinical trial called CIT-HD. They studied the effects of citalopram on attention, thinking, muscle movements, and daily activities, with the results varying in different analyses. The study lasted for 20 weeks and concluded in 2013. For more information about CIT-HD, please click here.

Ampakines^

Ampakines are a type of drug that have recently caught the eye of the scientific community for their potential to raise BDNF levels. Cortex Pharmaceuticals Inc. is actively developing and researching the use of ampakines for treatment of various neurological disorders, including HD.

(Simmons et al. 2010): Scientists treating HD mice with ampakines are finding promising results. HD mice injected with ampakines twice a day have normal levels of BDNF. Additionally, several other symptoms of HD, such as striatal atrophy and aggregation of the mutatnt huntingtin protein, were decreased by ampakine treatment. These scientists also tested the behavior of the mice to see whether ampakine treatment was helpful in fighting the effects of the HD mutation. The motor symptoms that HD mice display were significantly improved in HD mice that were given ampakine treatment before their symptoms had begun. Another symptom that HD mice and patients display – problems with memory – seemed to be aided by ampakine treatment. Further studies are needed to verify these findings, but this study and others suggest that ampakines are a promising avenue of research.

Cystamine^

Cystamine is a drug that might combat HD in several ways. Apart from the fact that it is thought to raise levels of BDNF, cystamine might also inhibit protein aggregation (the process by which ‘clumps’ of mutant huntingtin form), and has antioxidant properties. Raptor Pharmaceuticals is currently studying cystamine in phase II clinical trials. For more information on cystamine and the on-going clinical trial, please read the HOPES article here.

For further reading^

1. Connor, J. et al. (1997). Distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein and mRNA in the normal adult rat CNS: evidence for anterograde axonal transport. Society for Neuroscience 17(7): 2295-2313.

This article is fairly complex. It describes the likely method through which BDNF exerts its effects within the brain.

2. Gomez-Pinilla, F., Ying, Z., Roy, R., Molteni, R., & V. Edgerton. (2002). Voluntary exercise induces a BDNF-mediated mechanism that promotes neuroplasticity. J Neurophysiol. 88(5): 2187-95.

This article is easy to understand and it describes the effect of exercise on brain health and plasticity.

3. Vaynman, S., Ying, Z., & F. Gomez-Pinilla. (2003). Interplay between brain-derived neurotrophic factor and signal transduction modulators in the regulation of the effects of exercise on synaptic-plasticity. Neuroscience 122(3): 647-57.

This article is fairly easy to read and it discusses the possible mechanisms through which exercise may influence levels of BDNF.

4. Simmons DA, Mehta RA, Lauterborn JC, Gall CM, Lynch G. Brief ampakine treatments slow the progression of Huntington’s disease phenotypes in R6/2 mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2011 Feb;41(2):436-44.

A technical article that describes how ampakines raise BDNF levels in HD mice

5. Zuccato C. et al. (2001) Loss of huntingtin-mediated BDNF gene transcription in Huntington’s disease. Science, 293, 493-496.

This is a technical article that describes how the beneficial activity of huntingtin is lost in people with HD and how this leads to decreased production of BDNF.

6. Zuccato C., Tartari T., Crotti C., Goffredo D., Valenza M., Conti L., Cataudella T., Leavitt B. R., Hayden M. R.,Timmusk T., Rigamonti D. & Cattaneo E. (2003) Huntingtin interacts with REST/NRSF to modulate the transcription of NRSE-controlled neuronal genes. Nature Genetics 35: 76-83.

This article is very technical. It describes in detail how normal huntingtin increases transcription of BDNF by silencing NSRE.

D. McGee, 1-1-06, Updated by M. Hedlin 9.27.11 More

Verapamil is a currently available FDA-approved drug traditionally used to treat irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias) and high blood pressure by relaxing blood vessels. It has been discovered that verapamil can also modulate autophagy, a process by which cells gets rid of unwanted proteins and damaged cellular components. If this process is disrupted as it is in Huntington’s Disease (HD) and other neurodegenerative disorders then cellular “trash” can accumulate and harm brain cells. Thus, Verapamil’s effects on autophagy opens the door for its use in treating HD where the formation of protein aggregates is characteristic. To learn more about autophagy, click here. To learn more about the role of protein aggregates in HD, click here.

Verapamil was one of five L-type Ca+2 channel antagonists initially screened to test for its efficacy in modulating autophagy. L-type Ca+2 channels are specialized high-voltage ion channels found on the dendritic spines of cortical neurons. For more information about the different parts of the brain, see the brain tutorial here. Verapamil and other calcium channel inhibitors may regulate autophagy by limiting the amount of calcium that can enter the cell. High levels of intracellular Ca+2 can up-regulate autophagy by activating calpains, which are enzymes that aid in protein breakdown. Interestingly, some studies have found that calpain activity is increased in HD cells and can chop the mutant huntingtin protein into smaller fragments which allows it to enter the nucleus of neurons leading to toxicity.

Verapamil may block this toxicity by preventing calcium from entering the neuron. This lower concentration of calcium can reduce calpain activity, which can in turn increase autophagy. In HD, more autophagy means that more of the mutant huntingtin protein is cleared and fewer aggregates formed. To learn more about aggregate formation and its role in HD, click here.

The Promise of Verapamil in treating HD

Verapamil was tested for its ability to induce autophagy in several HD cellular and mouse models. To learn more about mouse models, click here. The first, and simplest model used was the cell model. Rat-derived neuronal cells were engineered to express huntingtin aggregates and some were treated with verapamil. Cells exposed to the drug showed a greater degree of aggregate clearance than cells that were not.

The next model used to explore the effects of verapamil on HD was the fruit fly, a commonly used model for many experiments. The development of the eyes in flies expressing the mutant huntingtin protein is altered, which causes the photorecetors to become disorganized and to degenerate. Flies given verapamil had less severe degeneration, than control flies did.

The next animal model of HD tested was the zebrafish. Zebrafish expressing mutant huntingtin form aggregates in their eyes and optic nerve. As in human HD, cells that form aggregates are more likely to die. Zebrafish administered verapamil had fewer aggregates.

Despite all of these experiments indicating a neuroprotective role for verapamil, the process for approving the use of verapamil in treating HD is still in very early stages. Although the results of preliminary studies are very promising, many more trials and more research needs to be done before using verapamil in HD treatments.

Further reading

- http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/medmaster/a684030.html

Gafni J., and L. Ellerby. “Calpain Activation in Huntington’s Disease.” Journal of Neuroscience. 2002 June; 22(12):4842-4849.

This technical paper explained how calpain activation breaks huntingtin protein into pieces small enough to enter the nucleus and lead to toxicity in HD cells.

- Sarkar S., et al. “Rapamycin and mTOR-independent autophagy inducers ameliorate toxicity of polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin and related proteinopathies.” Cell Death and Differentiation advance online publication, 18 July 2008; doi:10.1038/cdd.2008.110.

This review paper explained the relationship between aggregate formation in several neurological diseases and the role in autophagy in protecting against these diseases. It also explained several animal models of HD.

- Williams et al. “Novel targets for Huntington’s Disease in an mTOR-independent autophagy pathway.” Nature Chemical Biology. 2008 May;5(4):295-305

This paper explained the testing of a number of potential HD drugs though targeting the autophagy mechanisms within cells.

A. Pipathsouk, 5/21/2009

More

When the cause of a disease can be traced to having too many copies of a certain nucleotide triplet in the DNA, the disease is said to be a trinucleotide repeat disorder. Today, there are 14 documented trinucleotide repeat disorders that affect human beings**. Huntington’s Disease is part of this group.

cells control nucleus refined Nis base range neuropathy

Some of these 14 trinucleotide repeat disorders are more alike than others. While the symptoms and the affected body parts vary by disease, scientists consider two illnesses to be similar if they share the same repeated codon as their cause. Six of the 14 trinucleotide repeat disorders have little or no apparent similarity to each other, or to the 8 remaining diseases. These 6 are described in brief at the end of this section. The 8 remaining disorders, one of which is Huntington’s Disease, all share the same repeated codon as their cause: CAG. Since CAG codes for an amino acid called glutamine, these 8 trinucleotide repeat disorders are collectively known as polyglutamine diseases (“poly” being the Greek word for “many”). (For background information on codons and amino acids click here.)

Polyglutamine diseases have much in common: Each of them is characterized by a progressive degeneration of nerve cells in certain parts of the body (for background info on nerve cells, click here.) In each disease, this degeneration first disrupts the function of certain group(s) of nerve cells. After 10-20 years, many of the affected nerve cells die. The major symptoms of these diseases are similar to one another and they usually affect people around the same time, in mid-life (although childhood cases have also been reported, as in the case of juvenile HD).

It deserves to be reiterated that while the polyglutamine diseases are similar to each other, they are not identical. Although they share the same repeated codon (CAG), the repeats for the different polyglutamine diseases occur on different chromosomes, and thus on entirely different segments of DNA. (For more info on chromosomes, click here.) Despite this fact, scientists are excited about research in any of the polyglutamine diseases because finding a way to stop the CAG repeat from occurring in one disease may help lead to a cure for the other 7 as well. While this is by no means a certainty, the possibility offers wonderful incentive to be persistent in research; eight for the price of one would certainly be a great deal!

Below you will find detailed descriptions for each of the polyglutamine disease, as well as a general description of all the non-polyglutamine diseases.

**Although only 14 trinucleotide repeat disorders are well-documented in medicine, genetic analysis has led researchers to believe that others exist as well. These disorders are even less common than the well-documented disorders and so have been more difficult to study, which leaves much of their story untold. They will be omitted here.

Polyglutamine Diseases:

DRPLA (Dentatorubropallidoluysian Atrophy)

Like other trinucleotide repeat disorders, DRPLA (Dentatorubropallidoluysian Atrophy) affects both the mind and body. It is characterized by abrupt muscle jerking, involuntary movements, and eventual dementia. Although these symptoms are common in the men and women of all ages who have DRPLA, young people with the disease may also be affected by progressive intellectual decline.

The Gene:

The gene involved in DRPLA lies on Chromosome 12 and is also named “DRPLA”. Typically, in asymptomatic individuals there are between 6 and 35 copies of CAG in the DRPLA allele. In a person with the disease, however, the allele has anywhere between 49 and 88 copies. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with between 35 and 49 copies of CAG will have on individuals. To learn more about alleles and more specifically, HD alleles, click here.

The Protein:

The protein product of the DRPLA gene is called atrophin-1. Although scientists are not sure about its function, the leading theory is that atrophin-1 is involved in the pathway that helps insulin take effect in the body’s cells. Since insulin helps determine how cells utilize their energy, it is essential that this pathway work smoothly so that cells can function efficiently. If there is a kink in the plan, it could spell disaster for an affected nerve cell.

How the Symptoms Come About:

The nerve cells affected in DRPLA lie in many different parts of the brain. Understanding the functions of these different parts allows us to get a better understanding of why the symptoms of DRPLA are what they are: Take first the striatum and the globus pallidus. Together, these very important regions of the brain are collectively known as the basal ganglia. The basal ganglia are important because they help plan movements and thus have a large effect on motor control. Working with other parts of the brain such as the red nucleus and the dentate nucleus (which are also damaged in people with DRPLA), the basal ganglia help to regulate each and every movement we make. When neurons in this area are damaged due to DRPLA, it’s no wonder that muscle jerks and involuntary movements become common. (For a more detailed description of the basal ganglia – written in regards to Huntington’s Disease – click here). (See Figure F-1.)

The same can be said for damage to the cerebellum, which also occurs in people with DRPLA. The cerebellum is the region of the brain where learned movements are stored. When damage occurs here, movements that were once smooth and refined become more jerky and rough since they must be constantly relearned. (See Figure F-2.)

The cerebral cortex also has a large effect on movement, particularly through the parts of it called the motor cortex and somatosensory cortex. Thus, the cerebral cortex is also involved in the motor symptoms of DRPLA. However, the tasks of the cerebral cortex reach far beyond motor control. Consider the many amazing capabilities we humans have: keen senses, the ability to speak and understand language, and the fact that we can create and use such things as logic and reason. All of these characteristics stem from functions of the cerebral cortex. Thus, when damage occurs to specific parts of the cerebral cortex, the tasks that these parts work to accomplish may become less refined. This loss of refinement may explain why people with DRPLA experience dementia when the nerve cells in the cerebral cortex are damaged. It may also partly explain the general intellectual decline in juvenile cases of DRPLA. (See Figure F-3).

Huntington’s Disease (HD)

For an introduction to HD, click here.

SBMA (Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy)

SBMA (Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy) occurs predominantly in males and is characterized by weakness and atrophy of the proximal muscles. Difficulties with swallowing and articulating speech are also common symptoms of SBMA. As the first word of its name implies, the disease mainly affects the spinal cord (“spino-“) and a part of the brain called the bulbar region (“-bulbar”). (See Figure F-4.)

The Gene:

The gene involved in SBMA is called the Androgen Receptor (AR) gene. It is located on the X chromosome, which is one of the so-called sex chromosomes. (Unlike most of our chromosomes, the sex chromosomes differ between males and females and this is why SBMA occurs predominantly in males. To learn more about chromosomes, click here.) Typically, in asymptomatic individuals there are between 9 and 36 copies of CAG in the AR allele. In a person with the disease, however, the allele has anywhere between 38 and 62 copies. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with 37 copies of CAG will have on individuals.

The Protein:

Hearing the oft-repeated statement “DNA codes for proteins” might lead one to believe that it is as simple as show me DNA and poof!, you have a protein. Actually, the process is much more complex than that. In fact, the full sequence of events is broken up into several parts, one of which is called transcription. The Androgen Receptor gene codes for a protein of the same name, the Androgen Receptor (also abbreviated “AR”). Because the AR protein is a key player in transcription, it is aptly titled a transcription factor.

In its normal state, then, the AR protein helps cells carry out the instructions contained within DNA. (For more in-depth discussion of DNA and the genetic code, click here.) However, in people with SBMA, the protein has extra glutamines, resulting from the extra CAGs in the AR gene. Although scientists do not yet have a definitive explanation as to why the extra glutamines cause degeneration of the neuron, it seems likely that the extra glutamines create an altered form of the AR protein that does not perform its actions in the same way as the normal AR. This mechanism for degeneration of the neuron is much like the one for Huntington’s Disease, as illustrated in Figure A-3.

Another theory suggests that the degeneration of the nerve cell is a result of neuronal inclusions (NIs). This theory, too, has its equivalent in the study of Huntington’s Disease. (Click here for more about nerve cell death in HD). According to the theory, the extra glutamines in the protein have a way of attracting other proteins to group together with the AR. This aggregation of proteins causes clumps, or inclusions, which may be solely responsible for damage to the nerve cell. More research in this area is necessary to find out definitively if the NIs are the true cause of damage. (See Figure F-5.)

How the Symptoms Come About:

Whatever the mechanism, once the nerve cells become damaged, the symptoms of SBMA begin to appear. As mentioned above, one of the main areas of the body that SBMA affects is the spinal cord. More precisely, it affects the parts of the cord known as the anterior horn and the dorsal root ganglion. The dorsal root ganglion is a group of nerve cell bodies that pass sensory information to other spinal cord nerve cells and on to the brain for analysis. The anterior horn is a region of the spinal cord that contains cell bodies of motor neurons, which put the brain’s decisions (based on the sensory info) into action. These two regions of the spinal cord are thus essential for control of fine muscle movements. When the dorsal root ganglion is damaged, the brain cannot receive proper input and thus cannot plan a movement of the muscle. When the anterior horn is damaged, the brain’s planned movement cannot be carried out. Thus, if either of these regions is not functioning correctly, then the muscles are not able to carry out the same motions that they had always done before. This inability to perform normal motions is why muscle weakness and atrophy are so common in SBMA. (See Figure F-6.)

But the spinal cord is not the only body part affected by SBMA; the bulbar region of the brain is harmed as well. The bulbar region is composed of the cerebellum, the medulla and the pons. (For a tour of brain structures, including these three, click here.) An extension of the spinal cord at the base of the brain, the medulla and pons are responsible for some of the functions that keep us alive. Functions that we usually never think about, like breathing, blood circulation, and simple actions like swallowing are all in large part controlled by the medulla and pons. More complex functions, however, require use of the cerebellum. The cerebellum is where our learned movements are stored—it helps refine a great deal of motor activities, from throwing a baseball to speaking. Given the roles of the medulla, pons, and cerebellum, it’s no wonder why damage to these areas can cause difficulty swallowing and articulating speech, two more symptoms of SBMA. (See Figure F-7.)

SCA1 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1)

SCA1 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 1) is one of many closely related disorders collectively known as spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs). Like all of the SCAs, SCA1 is characterized by atrophy of the cerebellum, a phenomenon that plays a role in the major symptoms of the disorder like loss of coordination and difficulty in articulating speech. Another common symptom of the disorder is decreased sensation in the limbs.

The Gene:

The gene involved in SCA1 lies on Chromosome 6 and is also called SCA1. Typically, in asymptomatic individuals there are between 6 and 44 copies of CAG in the SCA1 allele. In alleles with more than 20 copies (but still less than 44), the codon CAT interrupts the string of CAGs 1-4 times in a way that adds stability to the CAG chain. In a person with the disease, however, these stabilizing CATs are not present and the allele has anywhere between 39 and 81 copies of CAG. Thus, especially in the 39-44 CAG repeat range (where one may or may not be at risk for the disease), the CATs are very important—their existence can make the difference between having the illness and not.

The Protein:

The protein product of the SCA1 gene is called ataxin-1. Many studies of ataxin-1 have led scientists to believe that its major function may be to facilitate the maneuvering of nerve cell connections to allow learning. However, it is important to note that the symptoms of SCA1 are not directly caused by the loss of normal ataxin-1 function. Instead, it is believed that the cause of disease lies in the interaction between ataxin-1 and another protein called LANP. Scientists believe that LANP has a major effect on cell communication, which is needed for the survival of a nerve cell. When the ataxin-1 is altered, its interaction with LANP is also altered. The ataxin-1 is said to “sequester” the LANP and thus interfere with its normal activity. After a time, the sequestering of LANP appears to cause degeneration of the nerve cell.

How the Symptoms Come About:

To best explain how the symptoms of SCA1 come about, it is helpful to have an understanding of the cerebellum. (For more on the cerebellum, click here.)

Add to the equation a loss of pyramidal nerve cells (cells of a different pathway that are also involved in performing highly-skilled motions) and one can see why SCA1 can have such a large effect on one’s ability to perform movements.

The decreased sensation in the limbs of people with SCA1 is known as peripheral neuropathy. This condition comes about when the nerve cells that pass information from the limbs to the spinal cord (and on up to the brain) are damaged. Since they cannot do their jobs to maximum effectiveness, some of the sensory information is lost and this results in the decreased sensation.

SCA2 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2)

SCA2 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2) is characterized by a general slowing of some of the body’s normal processes. In addition to the loss of coordination that is common to all SCAs, people with SCA2 often develop slow or nonexistent reflexes and tend to shift the focus of their eyes from one point to another in a very deliberate manner. Partial paralysis of the eyes has even been described in some cases.

The Gene:

The gene involved in SCA2 lies on Chromosome 12 and is also named SCA2. Typically, in asymptomatic individuals there are between 14 and 31 copies of CAG in the SCA2 allele. In a person with the disease, however, the allele has anywhere between 36 and 64 copies. Individuals with between 31 and 36 copies of CAG may or may not develop the symptoms of the disease (individual results vary).

The Protein:

The protein product of SCA2 is called ataxin-2. So far, although the exact function of this protein is unknown, scientists believe that it may be involved in aiding protein-protein interaction within the cell. This would make it something of a “mediator” of communications within the cell. If this theory is correct, then when the protein is in its altered form in people with SCA2, it cannot do the same mediation that the normal form does. This loss of normal function means that essential protein-protein interactions cannot be as efficient as they were with the normal ataxin-2 involved. The end result is that the health of the cell is compromised. (See Figure F-9.)

How the Symptoms Come About:

The mechanism for the loss of coordination experienced in SCA2, due primarily to damage to the cerebellum, is more-or-less the same as the mechanism described for SCA1. (Read more about the cerebellum by clicking here.) The symptoms involving the eyes, however, result from SCA2’s effect on a different part of the brain. This region is called the midbrain. The primary function of the midbrain is to control the movement of the eyes. When neurons in this area are damaged, the eye’s movements become slower than normal and even partial eye paralysis can occur. Both of these phenomena are symptoms of SCA2. (See Figure F-10.)

The effect of SCA2 on the reflexes is explained by the damage it inflicts on the granule cells. A granule cell is a specific type of nerve cell that forwards a great deal of information on to the cerebellum. Much of this information involves the positions and movements of the limbs, as well as what parts of the skin are being stimulated at any given time. In terms of reflexes, all of this information is very important. As an example, suppose that someone is burned by a hot plate: The person must know not only what body part this sensation is coming from, but also where this part is located in space and what direction to move it in order to stop the pain. If this information is slow in getting to the brain, it can delay the reflex that is needed to deal with the pain. This slower flow of information occurs when the granule cells are damaged, causing people with SCA2 to develop slower reflexes. (See Figure F-11.)

SCA3 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3 or Machado-Joseph Disease)

SCA3 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 3) is also known as Machado-Joseph Disease. In addition to the loss of coordination that is common to all SCAs, the most common symptoms of SCA3 include bulging eyes, small contractions of the facial muscles, and general rigidity.

The Gene:

The gene involved in SCA3 lies on Chromosome 14 and is also named SCA3 (although the name “MJD1” is sometimes used instead). Typically, in asymptomatic individuals there are between 12 and 43 copies of CAG in the SCA3 allele. In a person with the disease, however, the allele has anywhere between 56 and 86 copies. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with between 43 and 55 copies of CAG will have on individuals.

The Protein:

The protein product of SCA3 is called ataxin-3. Although scientists do not know the exact function of the protein, they do know that it normally resides in the cytoplasm of the cell. In people who have SCA3, however, ataxin-3 is known to aggregate in the nucleus. Researchers suspect that this change of place may be key in understanding the initiation of the disease. (See Figure F-12.)

How the Symptoms Come About:

Of all the polyglutamine disorders, SCA3 is perhaps the most perplexing with regard to the relationship between the affected brain regions and the symptoms of the disease. Damage commonly occurs in the cerebellum, basal ganglia, brain stem, and spinal cord. While damage to these areas commonly affects a wide range of movements, it does not seem to explain why such things as bulging eyes and general rigidity would occur. Hopefully, more research in this area will soon uncover the mystery.

SCA6 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 6)

SCA6 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 6) is probably the simplest of all the SCAs in terms of its symptoms: People with SCA6 predominantly experience random episodes of ataxia or slowly progressing ataxia.

The Gene:

The gene involved in SCA6 lies on Chromosome 19 and is also named SCA6. Typically, in asymptomatic individuals there are between 4 and 18 copies of CAG in the SCA6 allele. In a person with the disease, however, the allele has anywhere between 21 and 33 copies. This is the smallest number of trinucleotide repeats known to cause disease. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with 19 copies of CAG will have on individuals. Individuals with 20 copies of CAG may or may not be at risk of developing SCA6. To learn more about alleles and more specifically, HD alleles, click here.

The Protein:

Instead of its own separate protein product, the SCA6 gene codes for a subunit of the calcium channels that exist in all nerve cells. This subunit, called Alpha-1A, creates a pore in the membrane of the nerve cell, allowing calcium to enter the cell and have an excitatory effect. The excited cell can then process the inputs it has received (due to calcium’s effect) and decide whether or not it should relay this information on to other nerve cells. In this way, Alpha-1A appears to play a significant role in nerve cell communication. (For more information about how nerve cells communicate, click here). In their altered form, however, Alpha-1A subunits tend to leave the membrane and aggregate in the cytoplasm inside the cell, where they clump together and do not perform their normal duties. This movement from the membrane hinders the nerve cell’s ability to receive and process messages from other nerve cells. Since communication is essential to the survival of nerve cells, the clumping of the altered Alpha-1A subunits in the cytoplasm may play a significant role in nerve cell degeneration. (See Figure F-13.)

How the Symptoms Come About:

In SCA6, the areas most affected by nerve cell damage are the cerebellum and the Purkinje cells. Given their roles in refining motions (as mentioned in the discussion of the cerebellum), one can see how damage to these areas esults in loss of coordination. Also contributing to the symptoms is degeneration of the granule cells and the nerve cells of the inferior olive. Since these structures are involved in the input of information to the cerebellum – and likewise the Purkinje cells are involved in its output – we can see that both input and output are quite important in creating smooth, precise motions. At any given time, some nerve cells may be less affected by SCA6 than others, and this may account for the random episodes of ataxia: one group of cells may be affected one day, and another group a different day. (See Figure F-14.)

SCA7 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 7)

SCA7 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 7) is the last of the SCAs to fall under the category of polyglutamine diseases. Like the other SCAs, the most common symptom of SCA7 is loss of coordination. In addition to this, people with SCA7 often have difficulties with vision.

The Gene:

The gene involved in SCA7 lies on Chromosome 3 and is also named SCA7. Typically, in asymptomatic individuals there are between 4 and 19 copies of CAG in the SCA7 allele. In a person with the disease, however, the allele has anywhere between 37 and 306 copies. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with between 19 and 29 copies of CAG will have on individuals. Individuals with 30-36 copies of CAG are considered to be in the intermediate zone; they may or may not develop the symptoms of SCA7. If they do develop symptoms, the symptoms are likely to be milder and to appear later in life than they would for people with 37 or more copies of CAG.

The Protein:

The protein product of the SCA7 gene is called ataxin-7. Currently, the normal function of this protein is unknown. Scientists suspect that when ataxin-7 proteins are altered, they tend to clump together in the nucleus, producing what are called neuronal inclusions, or NIs (NIs have also been found in certain nerve cells of people with SBMA, HD, and some other SCAs). These inclusions have been associated with degeneration of the nerve cell, but whether or not they are in fact the direct cause of degeneration is yet to be determined. (See Figure F-5.)

How the Symptoms Come About:

The loss of coordination that people with SCA7 experience results from damage to the cerebellum. This mechanism is more-or-less the same as that of SCA1. (For a more detailed explanation of this mechanism, click here.)

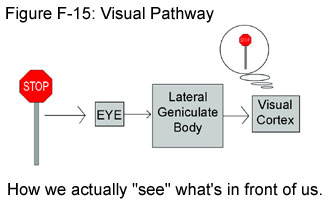

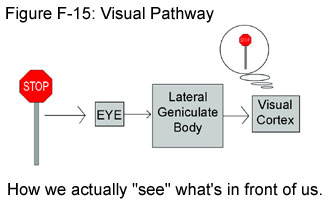

The effect that SCA7 has on one’s vision is a little more complicated because vision is a process that involves many players. Contrary to popular belief, humans do not literally “see” with their eyes. Instead, the eyes are simply the first stop on a pathway for visual information that will eventually lead to the processing of this information in the brain. After light from an image comes into the eye, the information it contains is encoded into nerve impulses by the retina. (For a discussion of nerve impulses, click here.) These impulses are then sent down the optic tract to a part of the brain called the lateral geniculate body. Here the information undergoes something like a preliminary inspection, which involves a categorization of the data. The newly categorized info is then sent on to the visual cortex, which is part of the cerebral cortex of the brain. It is in the cerebral cortex where the brain assembles a processed image and we actually “see” what is in front of us. To see an image clearly and accurately, then, all pieces in this visual puzzle must be in good working order. In SCA7, however, there is noticeable damage to all parts of the visual pathway. While this by no means implies that people with SCA7 go blind, some problems with vision are likely to occur. (See Figure F-15.)

Non-Polyglutamine Diseases

As noted in the introduction to this chapter, polyglutamine diseases are only a subset of the trinucleotide repeat disorders. As of this writing (summer 2001), researchers have identified six non-polyglutamine diseases that also fall under the category of trinucleotide repeat disorders. Because each disease involves a unique repeated codon, the six non-polyglutamine diseases show relatively little resemblance to one another. More importantly, none of them appear to have any strong similarity to Huntington’s Disease or the other polyglutamine diseases. For this reason, we provide only brief descriptions of these non-polyglutamine disorders. The descriptions follow below.

Fragile X Syndrome

Fragile X Syndrome (often abbreviated “FRAXA”) is a disorder involving the CGG codon (contrast this with the CAG codon involved in the polyglutamine diseases). The affected gene is called FMR1 and it lies on the X chromosome (hence the name “Fragile X Syndrome”). In asymptomatic individuals, the FMR1 allele has between 6 and 53 CGG repeats. In people with the disorder, the FMR1 allele has over 230 repeats. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with between 53 and 230 copies of CGG will have on individuals. Common symptoms of FRAXA include mental retardation, long and prominent ears and jaws, stereotypic hand movements (like flapping and biting one’s hands), hyperactivity, and others. The disease typically affects males.

Fragile XE Mental Retardation

Fragile XE Mental Retardation (often abbreviated “FRAXE”) is a disorder involving the GCC codon. The affected gene is called FMR2 and, like the gene causing Fragile X Syndrome, FMR2 lies on the X chromosome. In asymptomatic individuals, the FMR2 allele has between 6 and 35 copies of GCC. In people with the disorder, however, the allele has over 200 copies of GCC. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with between 35 and 200 copies of GCC will have on individuals. Common symptoms of FRAXE include mild mental retardation, learning deficits, and possible developmental delays.

Friedreich’s Ataxia

Friedreich’s Ataxia (often abbreviated “FRDA”) is a disorder involving the GAA codon. The affected gene is called X25 (also known as “frataxin”). In asymptomatic individuals, the frataxin allele has between 7 and 34 GAA repeats. In people with the disorder, the allele has 100 or more repeats. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with between 34 and 100 copies of GAA will have on individuals. There are many common symptoms of FRDA, some of which include slurred speech, heart disease, and diminished reflexes of the tendons. The name “ataxia” describes a loss of coordination, and this is typical in the limbs and trunk of those who have FRDA. The typical age of onset for this disorder is early childhood.

Myotonic Dystrophy

Myotonic Dystrophy (often abbreviated “DM”, not “MD”) is a disorder involving the CTG codon. The affected gene is called DMPK. In asymptomatic individuals, the DMPK allele has between 5 and 37 CTG repeats. In people with the disorder, the allele has at least 50 repeats in adult-onset cases, and can go up to several thousand in congenital cases. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with between 37 and 50 copies of CTG will have on individuals. Common symptoms of adult-onset DM include muscle weakness and degeneration, while such symptoms as kidney failure, facial dysmorphology, heart problems, premature balding, cataracts, and, in males, atrophy of the testicles are less common. The congenital form of DM is the most severe and its symptoms include diminished muscle tone, problems with respiration at birth, and developmental abnormalities. The term “myotonic” comes from “myotonia”—a condition characterized by frequent muscle spasms. Obviously, myotonia is quite common in DM.

Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 8

Like Myotonic Dystrophy, SCA8 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 8) is a disorder involving the CTG codon. The affected gene is also called SCA8. Asymptomatic individuals possess between 16 and 37 repeats of CTG in the SCA8 allele, while people with the disorder have between 110 and 250 repeats. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with between 37 and 110 copies of CTG will have on individuals. SCA8 is a slowly progressive disorder and its symptoms include decreased sense of vibration, sharp reflexes, and atrophy of the cerebellum, which has a large amount of control over the body’s learned movements. (For a more detailed description of the cerebellum, click here.)

Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 12

Much like the polyglutamine diseases discussed above, SCA12 (Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 12) is a disorder involving the CAG codon. But unlike the polyglutamine diseases, which have CAG repeats that occur in what is known as the “translated region” of DNA, the CAG repeats in SCA12 occur in what is called an “untranslated region” of DNA. In what basically amounts to an exception to the normal rule, the chemical information of an untranslated region of DNA is not used as instructions for making proteins. None of the codons in the untranslated region of DNA produce any amino acids at all (a realization that has prompted some scientists to refer to the untranslated region as “junk DNA”). This exception means that the CAG codons of SCA12 actually do not produce the amino acid called glutamine. Because of this fact, SCA12 is not considered a polyglutamine disorder.

The affected gene in SCA12 is also called SCA12. Asymptomatic individuals possess between 7 and 28 repeats of CAG in the SCA12 allele, while people with the disorder have between 66 and 78 repeats. At present, not enough data exist to fully understand the effect that alleles with between 28 and 66 copies of CAG will have on individuals. SCA12 is the most recent addition to the group of spinocerebellar ataxias. Since there are relatively few cases to date, the full effects of the disorder are not yet fully known. Given that it is a spinocerebellar ataxia, however, it is likely that some of the general symptoms include slurred speech and loss of coordination of some parts of the body.

For further reading

- Cummings, C. J. and Zoghbi, H.Y. “Trinucleotide Repeats: Mechanisms and Pathophysiology.” Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2000. 1:281-328.

A fairly technical paper explaining the symptoms of each trinucleotide repeat disorder, as well as a breakdown of the codon involved and the amount of repeats in people with and without the disease (as of the publishing, however, updated and slightly different data regarding the numbers are available; see next entry in bibliography). Also discussed are theories regarding the function of the altered proteins.

- GeneClinics. Online.

An in-depth site with very recent information about all of the SCAs (and DRPLA). A wonderful resource to find out more about each disorder. (Look up the any of the SCA’s by using the search feature.)

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM). Online.

A compilation of abstracts from a multitude of different studies on HD. From case studies regarding inheritance to new methods of diagnosing HD, this is an excellent site for all the various types of HD research going on today. (Look up any of the trinucleotide repeat disorders using the search feature.)

- Silverthorn, Dee Unglaub. “Human Physiology.” Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001. pp. 256-263, 396.

Written for college students, this textbook has excellent explanations of all aspects of human physiology, as well as wonderful pictures to increase one’s understanding. The pages noted are excellent in teaching the functions of various parts of the nervous system.

- Thompson, Richard F. “The Brain.” New York: Worth Publishers, 2000. pp. 11-16, 296-303, 308-309, 451.

An introduction to neuroscience. Very clearly explains the functions of the various parts of the nervous system. Also gives insight into current research going on in neuroscience.

-M. Stenerson, 9-25-01

More

In the last few years, stem cell research has become the latest buzz in the popular media as well as the scientific world. It was the subject of President George W. Bush’s first prime-time television address. It is continuously on the cover of popular news magazines. So what is all the fuss about?

Stem cells hold the potential to treat or even cure many of the diseases that continue to mystify scientists today, such as Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease, diabetes, and Huntington’s Disease (HD). However, stem cell research is controversial, as most of the stem cell lines available today are derived from embryos or fetuses.

basic ups

The following chapter aims to explain the science behind stem cells and their potential to treat HD.

Stem Cell Basics

What is a stem cell?

Most of the cells that make up the organs and tissues of the body are highly specialized for their specific jobs. The red blood cell, for example, is specifically crafted to carry oxygen from the lungs to the tissues. A comparison can be made with today’s society where most workers are trained to perform a specific trade. The days of the generic fix-it man are gone; instead, the electrician, the plumber, and the cable guy fill specific niches.

Likewise, in the human body, most cells are specialized for certain jobs. In fact, most cells lead very standard lives – they grow up, do the same job every day, and then eventually retire and pass away. These cells, such as nerve cells or skin cells, are called specialized cells. They are mature cells that have characteristic shapes and are committed to performing specific functions (See Figure 1). Once these cells have matured, they are usually incapable of reproducing themselves. They essentially remain “childless” for their whole lives.

If mature specialized cells cannot leave “children” behind when they die, how does your body make new cells? For example, when you cut your skin, how do you grow new skin cells? When you get blood drawn, how do you make new blood cells?

It turns out that stem cells solve this unique problem. A stem cell can reproduce itself over and over again (a special trick known as “self-renewal” or “self-replication”). With every replication, the stem cell produces one new stem cell and one new specialized cell. Stem cells can often give rise to a number of different cell types. For example, blood stem cells can produce both red blood cells and white blood cells. In this way, stem cells are not committed to produce a single cell type. Instead, a stem cell remains uncommitted until it receives a specific signal to divide and produce one of the various specialized cells.

In more formal terms, a stem cell is a special kind of cell that has the ability to divide for indefinite periods of time and to give rise to the mature, specialized cells that make up an organism. A stem cell is uncommitted and remains uncommitted until it receives a signal to differentiate (become a specialized cell). (See Figure 2).

What are the different kinds of stem cells?

There are three main types of stem cells under scientific study today:

- Embryonic stem (ES) cells: ES cells are taken from the very early stages of embryo development and can give rise to all of the cells of the human body, except the placenta and other supportive tissues in the womb.

- Embryonic germ (EG) cells: EG cells are taken from the later stages of embryo development and are slightly less “powerful” in their ability to divide.

- Adult stem cells: Adult stem cells are found in the tissues of a fully developed child or adult and can only produce a limited number of cell types.

These three types of stem cells are easiest to understand in a discussion of human development. Human development begins when a sperm fertilizes an egg and creates a single cell, known as a zygote, which has the potential to form an entire organism. This single cell is said to be totipotent, meaning it has the “total” potential to give rise to all types of cells. About 24 hours after fertilization, the zygote divides into two identical totipotent cells, and is now known as an embryo. About five days after fertilization and after several cycles of cell division, these cells begin to specialize and form a hollow sphere, called a blastocyst. The blastocyst has an outer layer of cells that make up the shape of a sphere and a cluster of cells, known as the inner cell mass, inside the sphere. The outer layer of cells will eventually form the placenta. The inner cell mass will eventually form all the tissues of the human body. The inner cell mass cannot form an organism on its own, however, because it is unable to produce the placenta and the other supporting tissues necessary for development in a woman’s uterus. Therefore, the inner cell mass cells are said to be pluripotent, meaning they have the potential to give rise to most of the tissues required to produce an organism. In other words, they can give rise to all the cells of the human body, excluding the supportive tissues used in the womb. (See Figure 3).

Embryonic stem cells, which are also pluripotent, are isolated directly from the inner cell mass at this blastocyst stage. In 1998, researchers first isolated ES cells from human embryos that were obtained from in vitro fertilization clinics. Although these embryos were originally intended for reproduction, they were in “excess” and were headed for the trash. Instead of being disposed, however, they were donated to research.

Five to 10 weeks after fertilization, the growing embryo, now called a fetus, develops a region known as the gonadal ridge. The gonadal ridge contains the primordial germ cells, which will eventually develop into eggs or sperm.

Embryonic germ cells are isolated from these primordial germ cells of the 5- to 10- week old fetus. Like ES cells, EG cells are also pluripotent.

As the human fetus continues to develop, pluripotent stem cells specialize into stem cells that are geared for specific tissues. For example, they become blood stem cells (which produce blood cells) or skin stem cells (which produce skin cells). These specialized stem cells are said to be multipotent, meaning they can give rise to many, but not all, types of cells.

While all three types of stem cells discussed above (ES cells, EG cells, and multipotent stem cells) are found in the developing human, only multipotent stem cells are found in children and adults. Therefore, multipotent stem cells are often referred to as adult stem cells. Unlike other stem cells, adult stem cells are only found in specialized tissues and can only give rise to the specialized cell types that make up that tissue. Currently, adult stem cells have been found in the bone marrow, blood, blood vessels, skeletal muscle, skin, lining of the digestive track, dental pulp of the tooth, liver, pancreas, cornea and retina of the eye, and brain.

Stem Cell Research

What kind of research is being conducted?

Stem cells are being investigated in various areas of scientific research. The most notable research areas are described below:

I. Basic Research

On the most fundamental level, stem cells are used to study the early events of human development. This research may one day explain the cause of birth defects and help devise new approaches to correct or prevent them. Also, research on the genes and chemicals that control human development may help researchers manipulate stem cells to become specialized for transplantation or genetic engineering.

II. Transplantation Research

Stem cells may hold the key to restoring many vital bodily functions by replacing cells lost in various devastating diseases. Many diseases and disorders, such as Huntington’s disease, disrupt specific cellular functions or destroy certain tissues in the body. The goal, therefore, is to coax stem cells to develop into the desired specialized cells, which can then be used as a renewable source of replacement cells or tissues. This process could possibly treat HD and other conditions such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, spinal cord injury, stroke, burns, heart disease, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

III. Genetic Engineering Research

Stem cells could be used as a vehicle for delivering genes to specific tissues in the body. The goal is to add genes to stem cells that would then coax the stem cell to differentiate into a specific cell type or force the stem cell to produce a desired protein product. Currently, researchers are trying to use specialized cells derived from stem cells to target specific cancer cells and directly deliver treatments that could destroy them.

IV. Drug Testing and Toxin Screening

Currently, animal models are used to test drug safety and efficacy and to screen potential toxins. Animal models, however, cannot always predict the effects that a drug or toxin may have on human cells. Therefore, if human stem cells can be used to generate cells that are important for certain drug or toxin screenings, these cells may offer a safer, more reliable test by mimicking a more realistic human environment.

V. Chromosomal Abnormality Testing

Stem cells might also be used to explore the effects of chromosomal abnormalities in early human development. As a result, we might be able to understand and monitor the development of early childhood tumors, many of which are embryonic in origin.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of using embryonic stem cells, embryonic germ cells, and adult stem cells for research?

At first glance, embryonic stem cells, embryonic germ cells, and adult stem cells all present similar possibilities for scientific research. They are all stem cells, after all, and therefore share some key characteristics and hold similar potential. For example, they all have the ability to self-replicate for indefinite periods of time in the human body and can give rise to specialized cells. The overall purpose behind research with all types of stemm cells, therefore, is very similar. It has also been shown that all three cell types can be isolated from other cells and kept in a specific laboratory environment that keeps them unspecialized. This is crucial for controlled scientific research. Upon experimentation, it has also been shown that all stem cell types will replicate and specialize when transplanted into an animal with a lowered immune system. The cells then undergo “homing,” a process where the transplanted cells are attracted to and travel to an injured site when transplanted into an animal that has been injured or diseased. Homing provides hope that the transplantation of stem cells will be a clinically useful procedure.

Despite these general similarities, there are some important differences between embryonic stem cells, embryonic germ cells, and adult stem cells. The origins of these three cell types define their differences: ES cells are derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst in a developing embryo, EG cells are obtained from the primordial germ cells of a fetus, and adult stem cells are found in developed, specialized tissues. The differences between ES, EG, and adult stem cells result in different advantages and disadvantages for each stem cell type in scientific research and development.

ES and EG cells have some clear advantages over adult stem cells concerning research and clinical usefulness. For example, ES and EG cells are pluripotent, meaning they have the potential to give rise to all types of cells in the body. Adult stem cells are multipotent, meaning they only have the potential to give rise to a limited number of cell types. So far, no adult stem cells have proven to be pluripotent. This means that ES and EG cells could potentially provide a renewable source of replacement cells for any tissue in the human body. Adult stem cells, however, would only be clinically useful for the specific adult tissue that the stem cells came from. ES and EG cells are also relatively abundant in the developing organism, especially compared to adult stem cells, which are scarce in the adult body. As a result, ES and EG cells are much easier to identify, isolate, and purify compared to adult stem cells, which are very difficult to identify, isolate and purify in the lab. This makes research with ES and EG cells all around easier than research with adult stem cells.

On the flip side, adult stem cells have some distinct advantages over ES and EG cells. For example, adult stem cells are around for an organism’s lifetime, while ES and EG cells are only found in the developing organism. This allows a longer time frame for adult stem cells to be studied in an individual. Also, removal of stem cells from an embryo will result in the death of the embryo. Removal of adult stem cells, however, does not involve the death of an embryo, and is therefore less ethically complicated. Furthermore, adult stem cells pose no chance of immune rejection after transplantation because they can be transplanted back into the adult that they came from. ES and EG cells are derived from embryos and fetuses, however, and are transplanted into people with different genetic make-ups. Therefore, rejection is an issue only with the use of ES and EG cells.

Finally, ES cells have a strong advantage and disadvantage over the other stem cell types. First, ES cells are able to replicate in the laboratory far better than either EG or adult stem cells. ES cells can self-renew for up to 2 years, doubling up to 300 times. EG cells can only double a maximum of 70-80 times. Meanwhile, adult stem cells only have a limited ability to replicate in the lab. Replication in the laboratory is critical for research to continue. On the other hand, ES cells are the most likely to develop into tumors. If undifferentiated ES cells are taken from the lab and injected into a mouse, a benign tumor can develop. For this reason, scientists do not plan to use undifferentiated ES cells for transplants or other therapeutic applications. EG cells do not form these tumors, however. At this point, it is not known whether tumors will form with transplanted adult stem cells.

The similarities and differences of ES, EG, and adult stem cells are summarized in the chart below:

Which are more useful – pluripotent stem cells or adult stem cells?

Based on what scientists currently know, it is unclear whether pluripotent or adult stem cells will be more useful for the development of therapies. As far as scientists can tell at this point, neither one is probably better than the other.

Both pluripotent and adult stem cells have their advantages and disadvantages (see chart below). For example, the main advantage of pluripotent stem cells is their ability to produce any specialized cell in the human body. However, because they are derived from human embryos or fetuses, they are also very controversial.

Adult stem cells, on the other hand, are unlikely to be rejected by a patient’s immune system because they can be isolated from a patient, coaxed to divide and specialize, and then transplanted back into the patient. Because stem cells are isolated from an adult, they are also unlikely to cause ethical concerns. However, adult stem cells have not been isolated for all tissues of the body, which limits the types of tissues they can be used for.

Recently, there has been research on adult stem cell plasticity, the ability of an adult stem cell from one tissue to generate specialized cells of another tissue. Thus far, there have been contradicting results. Time will tell whether or not adult stem cells can actually demonstrate plasticity. For more information on cell plasticity, click here.

Many scientists agree that pluripotent and adult stem cells might be better suited for different treatments

What challenges are researchers facing?

While stem cell research shows great promise, researchers continue to face many biological, technological, and ethical challenges that must be overcome before innovations can be developed and incorporated into clinical practice.

First, more basic research must be done in order to fully understand the events that lead to cell specialization in humans. Currently, scientists are working to produce reliable, reproducible conditions that will direct stem cells to become the specific types of cells and tissues that are needed for transplantation.

Also, before mature cells derived from ES or EG stem cells can be used for transplantation, scientists must overcome the problem of immune rejection. Because these cells are genetically different from the recipient, their incompatibility must be minimized.

Adult stem cell research has also faced many difficulties, including finding, isolating and identifying the cells, growing the adult stem cells in the laboratory and demonstrating plasticity.

In addition to these technological challenges, researchers must also face the ethical controversy surrounding the use of ES and EG cells. If stem cells are used in clinical practice, researchers, doctors, and society at large must agree on acceptable ethical guidelines.

Stem Cell Research and Huntington’s Disease

What is the potential for using stem cells to treat HD?

Huntington’s Disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by the death of nerve cells in the striatum. (To learn more about the neurobiology behind HD, click here.) Until recently, it was believed that neurons in the adult human brain and spinal cord could not regenerate. Once dead, the neurons were thought to be gone for good. In the mid-1990s, however, researchers discovered that stem cells in the adult brain could give rise to new neurons and neural support cells. With their ability to regenerate and produce new nerve cells, neural stem cells might be able to replace or repair the cells that are destroyed by HD, thus restoring lost function.

In fact, researchers have already discovered how to coax embryonic and adult mouse stem cells to develop into neurons that produce a neurotransmitter called gamma-aminobutyric acid – the type of neurons that are mainly lost in HD.

More research could potentially lead to the following:

- If these stem cells can produce nerve cells in the laboratory, they could be transplanted into the striatum to replace the lost nerve cells, or;

- If the adult stem cells already present in the patient’s brain could be stimulated to produce more neurons, they might be able to “self-repair” the striatum.

Either way, further stem cell research could yield new treatments to HD given enough time, research, and luck.

What is fetal neural transplantation? What does this have to do with HD and stem cells?

Fetal neural transplantation is a surgical technique that involves removing nerve cells from an aborted fetus and transplanting them into a human patient. Clinical trials have attempted to use this technique as a treatment for HD by removing striatal nerve cells (those mainly affected by HD) from a human fetus and grafting them into the brain of an adult patient. The therapeutic value of fetal transplantation has been promising so far. Notable improvements include increases in brain activity and motor and cognitive functions. Although the initial results have been encouraging, the clinical usefulness of fetal neural transplantation for HD treatment remains unclear.

The use of human fetal tissue creates a major roadblock to the development of this technique for two reasons. Technically, fetal tissue is difficult to obtain and prepare. Ethically, the use of fetal tissue raises serious concerns. Therefore, the development of an alternative source of nerve cells for neural grafting will be crucial for the continuation of neural transplantation research. Stem cells currently hold great potential as an alternative source. Theoretically, neural stem cells could be developed in the laboratory and then grafted into the patient’s brain. Ultimately, the future of fetal neural transplantation as a clinically effective HD therapy relies heavily on the future of stem cell research.

Will stem cell research provide the cure for HD?

Researchers generally do not believe that stem cell research will be the “magic cure” for HD. Rather, it is likely to be part of the fight against the neurodegeneration seen in HD. Ultimately, the medical and scientific community will need to improve early diagnosis, reduce the severity of cell loss, combat inflammation, provide new neurons (which is where stem cells factor in), and utilize progressive rehabilitation techniques to allow complete regeneration. While stem cells may not cure HD, they could serve as a crucial component to effective treatment.

For further reading

- Allison, Wes. “Preliminary success of fetal brain-cell transplantation in Huntington’s Disease.” The Lancet.

A short, but fairly technical article.

- Begley, Sharon. “Cellular Divide.” Newsweek, 9 July 2001: 22-27.

An easy-to-read explanation of stem cells and an update on progress as of July 2001.

- Bjorklund, Anders and Ollie Lindvall. “Cell replacement therapies for central nervous system disorders.” Nature Neuroscience, June 2000, 3 (6): 537-544.

A technical paper discussing the progress of fetal neural transplantation in treating Parkinson’s and Huntington’s Disease.

- Freeman, Thomas, et.al. “Tranplanted fetal striatum in Huntington’s disease: Phenotypic development and lack of pathology.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 5 December 2000, 97 (25): 13877-13882.

A highly technical paper discussing the potential of fetal neural tissue to treat HD.

- Gibbs, W. Wayt. “Biological Alchemy.” Scientific American, February 2001: 16-17.

A less technical article depicting the discovery of neural adult stem cells and discussing the possible plasticity of adult stem cells.

- Mitchell, Steve. “Rare stem cells produces many cell types.” United Press International, 21 June 2002.

A short, easy-to-read article about adult stem cell plasticity.

- “Stem Cells: A Primer.” National Institutes of Health, May 2000.

A comprehensive, easy-to-read explanation of stem cells and their potential applications. Great online resource.

- “Stem Cells: Potential for Good?” The Economist, 18 August 2001: 59-61.

A thorough explanation of stem cells and the controversy surrounding their development and use.

- “Stem Cells: Scientific Progress and Future Research Directions.” Department of Health and Human Services, June 2001.

An extensive, fairly technical summary of everything you would want to know about stem cells.

- Weiss, Samuel. “Stem Cells and Huntington Disease.” Horizon, Huntington Society of Canada Newsletter, Summer 2001, No. 101: 1-2.

An easy-to-read explanation of stem cells and their potential to treat HD.

-J. Czaja, 3-07-03

More

Readers of our website sometimes ask, “Where does all the research summarized by HOPES come from?” Here follows a list of some main contributors to HD research, along with some of their recent studies, clustered in five categories:

We’ve also included some news articles highlighting the key discoveries. You will notice that the “Recommended Reading” list at the end draws directly from medical journals, so please be forewarned: the material there may be complex.

Ph

Biological Basis of HD

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/psychiatry/specialty_areas/huntingtons_disease/index.html

Director: Christopher A. Ross, M.D., Ph.D.

- Discovered a gene that, when mutated, causes a disorder called “Huntington’s disease-like 2,” or HDL2, which is very similar to HD.

- Found a way to make the CREB binding protein (a protein involved in the neuronal effects of HD) harmless by cutting out certain molecular areas.

- Determined that HD causes movement abnormalities by preventing the basal ganglia in the brain from correcting its mistakes.

Representative News Article:

http://www.jhu.edu/~gazette/2002/28oct02/28novel.html

University of California, Irvine

- Found that a certain protein called arfaptin 2 can prevent the huntingtin protein from aggregating, although it is still unclear whether or not these aggregates cause HD.

- Discovered that a class of drugs called “histone deacetylase inhibitors” can actually prevent, and in some cases reverse, brain cell death in fruit flies.

Representative News Article:

https://news.uci.edu/briefs/thompson-studies-point-to-new-targets-for-huntingtons-disease-treatments/

Weill College of Medicine at Cornell University

- Used metabolism studies to show that mice who have the HD allele do not use energy as efficiently as normal mice do.

University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine

- Used fruit flies to show that certain protein chaperones may suppress HD.

- First to discover that HD causes proteins to aggregate in the brain.

Stanford University

- Found that huntingtin aggregates cause proteasomes to malfunction, which creates problems when toxic proteins collect.

- For more information about research at Stanford, click here.

Mayo Clinic

- Researched why mutant proteins cannot be degraded in patients with HD.

HD Genetics

Indiana University School of Medicine

- Sends researchers to Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela, a community that has a high number of related individuals who are predisposed to developing HD. Researchers obtain specimen samples and test neurological functions to determine the genetic inheritance of HD.

University of Southern California

- Studied the Lake Maracaibo community and found that HD is caused by many genetic mutations that happen during mitosis—not just one in meiosis—and that the number of CAG repeats on the HD allele increases as the mutations accumulate over time.

Massachusetts General Hospital

- Found that certain types of brain cells tend to appear in higher densities in people who have a family history of HD.

- Studied the effects of HD on the transcription of genes across generations.

The Search for Treatments

Massachusetts General Hospital

- Tested coenzyme Q10 as a potential treatment for HD, and found that the drug can extend patients’ lives and delay the onset of symptoms.

- Performed an inconclusive clinical trial of riluzole, a drug that had been shown to improve motor abnormalities in HD-afflicted baboons. Investigations of riluzole continue.

National Institutes of Aging (NIA)

- Recently found that periods of fasting decreased the symptoms of HD in mice. Low-calorie diets and reduced meal frequency can both delay the onset of HD and slow down the spread of the disease.

Representative article:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2003/02/030211072836.htm

University of South Florida Center for Aging and Brain Repair

- Found that people whose diets are rich in antioxidants age slower because antioxidants block the free radicals that cause body function to decline.

- Successfully slowed aging in the brain by implanting stem cells from human umbilical cord blood.

- Discovered that when fetal tissue is implanted in the brains of HD patients, the new tissue remains free of HD.

Representative articles:

http://www.mcleanhospital.org/PublicAffairs/20001130_huntingtons.htm

http://www.cnn.com/2001/fyi/news/08/09/fetal.cell/

Stanford University

- Challenged the relationship between protein aggregates and HD with the discovery that drugs such as cystamine can reduce the symptoms of HD without affecting aggregates.

Weill College of Medicine at Cornell University