Genetic testing for Huntington’s Disease raises common questions on how the results could potentially impact access to health insurance. A recent study showed that patients often decide to pay out of pocket for medical service expenses due to the fear of losing their health insurance. Alleviating this worry of health insurance loss may help many who are hesitant to pursue genetic testing for financial reasons. Very little data is available on the indirect and out-of-pocket costs of HD in the US; however, a clinical study that is currently underway aims to bridge this gap. The study will use a cross-sectional online study administered to Huntington disease gene expansion carriers (HDGECs) by HD stage to understand these costs. The study is estimated to conclude on December 31, 2021; more information can be found here.

Health Insurance

The Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act

In trying to address discriminated based on genetic testing results, Congress passed the Genetic Information Non Discrimination Act (GINA) in 2008. This law protects individuals against health insurance and employment discrimination based on genetic testing resuls. Due to GINA, employers and health insurers are prohibited from making employment decisions or coverage determinations based on knowledge that an individual has received genetic services. The passage of GINA also means that genetic information is now treated as health information under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), making genetic information subject to HIPAA’s privacy regulations. GINA includes two sections, or “Titles”:

- Title I prohibits health insurance companies and group health plans from denying coverage or charging a higher premium based on genetic information(2).

- Title II prohibits employers from using an employee’s genetic information to discriminate when making employment decisions about hiring, firing, promotion, or terms of employment(2).

GINA only provides protection under health insurance and Medicare. It is important to note that after qualifying for Social Security Disability Insurance, individuals with Huntington’s disease must wait another 24 months before receiving benefits under the Medicare program. The Huntington’s Disease Parity Act (HR. 2589) has been recently introduced and currently advocated for to waive the two-year waiting period for Medicare coverage for those affected by Huntington’s disease. Providers of other types of insurance – long- term care insurance, disability insurance, and life insurance – may still request genetic information to determine eligibility and other coverage terms. If an individual is insured under a group health plan, the insurance company cannot change terms due to manifestation, or the development of symptoms of HD. However, if an individual is insured under an individual health plan, then an insurance company reserves the right to change terms.

The Exceptions to GINA

Although the signing of GINA created expectations that health insurance providers will not discriminate based on genetic information, this law does not prohibit insurance providers from rejecting applications or charging higher rates for people who have a medical diagnosis, such as HD(. Additionally, health insurance organizations may request the results of a genetic test for purposes of determining payment or reimbursement. Specifically, when a physician or other health care professional providing a health care service deems that the appropriateness of a medical treatment depends on an individual’s genetic makeup, the insurance providor is permitted to request that the insured individual undergo a genetic test. Although the individual reserves the freedom to accept or deny this request, if they refuse to undergo the genetic test, then the insurance provider reserves the right not to pay for their medical treatment. The insurance company also has the ability to adjust the individual’s payments based on the outcome of the genetic test, if the individual chooses to undergo genetic testing.

Additionally, GINA allows health insurers or group health plans to request – but not require – an individual to participate in genetic testing for research purposes. In this case, GINA requires a request to be written and communicated clearly with an at-risk individual or family member. It states that the compliance of the individual to undergo testing and participate in the study must be voluntary. Individuals also reserve the right to stop participating in any study at any time without consequences.

Social Security Disability Insurance

Social security disability insurance (SSDI) is intended to pay benefits to those with a disability when they are no longer able to work. To qualify for Social Security disability benefits, an individual must be able to prove that they are disabled to the point that they cannot reasonably continue to work in any form of gainful employment. SSDI determines coverage based on work credits, which is determined by the number of years you have worked and paid taxes into the federal system. Age also contributes to determining the number of years needed to qualify for benefits.

You can find more information about disability insurance here.

Long Term Care Insurance

Long term care (LTC) insurances are designed to pay a daily rate that assists in covering the costs of care when an individual has a chronic medical condition and/or a disability, such as HD. More specifically, this insurance assists with nursing home and/or adult day care expenses, assisted living costs, and in-home care and home modification expenses, such as wheelchair ramps. The daily rate a person receives will depend on the extensiveness of the LTC policy purchased, as well as their age when they apply. Unfortunately, GINA does not apply to LTC insurance; this means that LTC insurance companies reserve the right to deny someone insurance based on their genetic risk, gene status, or disease state(7). However, it is possible to avoid this risk by enrolling in LTC insurance prior to pursuing genetic testing. LTC insurance companies may reserve the right to request family history (i.e. HD) when enrolling, although some may not require this information. While Medicare does cover a short-period care if an individual requires skilled services or rehabilitative care (i.e. after a surgery), it does not pay for in-home care or non-skilled assistance with Activities of Daily Living (ADL), which make up the majority of long-term care services.This limits which facilities a person can consider. Due to State Partnership Programs that link special Partnership-qualified (PQ) long-term policies provided by private insurance companies with Medicaid, Medicaid does cover a share of long-term care services due. However, minimum state eligibility requirements based on the amount of assistance an individual will need with ADL, as well as income level requirements must be met. Additionally, while employee-sponsored insurance or private health insurance plans offered by a company may include an LTC component, it is often limited to skilled, short-term, medically necessary care.

Another option is to pursue a private insurance company that offers LTC insurance. As “private pay” consumers, LTC insured individuals often have more autonomy in their provider of care or services, as long as they are licensed companies. According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, most insurance policies define a pre-existing condition as “one for which you received medical advice or treatment or had symptoms within a certain period before you applied for the policy.” This specific time period varies between LTC insurances. Additionally, it is common for companies to require individuals to submit a physical. Because insurance companies may not be familiar with the physical implications of HD and genetic testing, it is important to inquire about what the exam results would entail under the LTC policy they offer. Companies may also not pay LTC related benefits for a period after the policy goes into effect. This period, which is usually 6 months long, is known as the “elimination period”, and varies between insurance policies. Some companies may not have pre-existing condition periods at all.

You can find more information about long term care insurance here.

Life insurance

Varying access to life insurance among individuals diagnosed with a degenerative disease stems from variable life expectancies. Despite the fact that someone diagnosed with HD will typically live between 10-30 years from the date of their diagnosis, individuals with a diagnosis do not qualify for a “traditional term” or “whole life” insurance policy. Some life insurance policies may offer accelerated death benefits (ADBs), which allow an individual to receive a tax-free advance on their life insurance death benefit while they are still alive, typically at the cost of a higher premium. Most, if not all, life insurance companies limit the options of at-risk or diagnosed individuals to an option known as guaranteed-issue life insurance.

Guaranteed-Issue life insurance

Guaranteed-issue life insurance is a policy available for all US citizens between the ages of 40-85, meaning genetic test results will not affect eligibility for this insurance policy. Guaranteed-issue life insurance policies do not require an individual to provide any information regarding their medical history or current health. While guaranteed-issue life insurance policies insure all qualifying individuals, they also have drawbacks such as “graded death benefits”. Graded death benefits are clauses written into a guaranteed-issue life insurance policy that limit when an individual’s life insurance policy will begin to cover them for natural causes of death. A typical graded death benefit will state that an individual must remain alive for at least 2-3 years after purchasing their guaranteed issue policy before qualifying for their coverage of a “natural” or “illness based” death. Additionally, guaranteed-issue life insurance policies are often more expensive than traditional types of life insurance, and are specifically designed to cover final expenses; it is unlikely that a diagnosed individual will find a policy that covers expenses beyond this, such as covering family supplemental income.

Final Expense Insurance and Burial insurance

Final expense insurance is intended to cover burial expenses, such as a grave marker and cemetery plot, and other final expenses, such as any outstanding debts that are not forgivable upon death. Since life expectancies for every person with HD varies, most burial insurance companies will only write guaranteed-issue life insurance policies for people diagnosed with HD, oftentimes at a higher cost. Typically, guaranteed-issue life insurance policies have a 24 month waiting period before covering these final expenses. If an insured individual passes during the first two years, the insurance company will refund all the cost, plus interest. This insurance policy usually ranges between $5,000 to $25,000 to cover expenses.

Burial insurance, or “funeral insurance policy”, is intended to cover burial or funeral home expenses. Once an insured individual passes away, the policy provides this coverage, usually ranging from $5,000 to $25,000. The biggest difference between final expense insurance and burial insurance is that final expense insurance typically includes final expenses in addition to the cost of a burial. Burial insurance is solely intended to cover the costs of funeral expenses.

Housing

There are federal or state programs that pay for housing for people above a certain age with low or moderate incomes, specifically less than $46,000 if single or $53,000 if married. The programs will review an individual’s monthly income and expenses on a regular basis to verify eligibility. Under these programs, recipients are allowed to live in their own apartments within approved complexes. To find out more about subsidized housing in your area, visit the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development-Subsidized Housing website here.

Another option is assisted living facilities, which provide room and board, social and recreational activities, and help with personal care and ADLs. Residents are expected to pay for the cost of medical and nursing services separately. There is also the option of a continuing care retirement community (CCRC), a community living arrangement, typically on a single campus, that provides housing, health care, and social services. CCRCs offer different levels of services ranging from independent housing to nursing home care. CCRCs charge a monthly fee based on the size of a person’s independent living unit, and an entrance fee. Some CCRCs may also require a health screening before a potential resident can move into a unit, and may allow the resident to hire their own home health care services while residing in an independent living unit.

More

Near the conclusion of 2018, Roche and Genentech announced that the first ever Phase 3 clinical trial to test a huntingtin-lowering drug would begin in 2019 . After Phase1 and 2 trials that test the safety and effectiveness of a new drug are performed, Phase 3 trials aim to demonstrate whether or not a drug candidate offers a treatment benefit to a population of interest (in this case, HD patients). The study was named “GENERATION -HD1” after the research team was inspired by HD families to hope that “this will be the last generation to suffer” . The acronym stands for “Global EvaluatioN of Efficacy and Safety of Roche/Genentech AnTIsense OligoNucleotide for Huntington’s Disease.” The study aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of an intrathecally administered drug called RG4042, or tominersen, in adult patients with manifest HD.

In an initial Phase I/II trial done by Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Roche, tominersen was shown to significantly reduce the levels of mutant HTT protein, the protein affected by the mutation responsible for HD, in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), the liquid surrounding the brain and spinal cord, of early stage patients . Some participants who received either of the two highest doses showed an average reduction of 40% in HTT levels in their CSF, while others experienced even greater reduction of up to 60%. Dr. C. Frank Bennett, senior vice president of research and franchise leader for the neurological programs at Ionis Pharmaceuticals mentioned in a press release that “… We were pleased that this antisense approach, which targets all forms of the huntingtin protein, proved to be safe and well tolerated in this study”.

This study was followed by a “GEN-PEAK” Phase I trial, which aimed to test the pharmacokinetics, or how the body affects a medicine, and pharmacodynamics, which assesses the interactions between the body and a compound, of tominersen when injected directly into the spinal canal . This trial was placed on hold after two cases of infection occurred during the study; however, the infections resulted to be linked to the device used to take samples of patients’ CSF and not to due to tominersen. Currently, the trial is actively recruiting 20 participants at sites in the Netherlands and United Kingdom.

Given the promising results from initial phase I/II trials that helped researchers understand an appropriate and safe treatment dose, the GENERATION -HD1 phase III study was launched to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of tominersen when given every 2-4 months over a period of 25 months. The study has enrolled 909 patients with manifest HD at around 80-90 sites in approximately 15 different countries around the world, including 20 sites in the U.S. and six in Canada. Prior to official acceptance into the study, all candidates were required to undergo a medical screening to check for any serious medical conditions, abnormal vital signs, or irregular general laboratory tests.

GENERATION -HD1 is a randomized, placebo-controlled study. This means that the participants will be randomly assigned to either the “experimental group”, or the group that will receive tominersen treatment, or the “control group”, or the group that will receive the placebos. A placebo is a harmless version of the treatment designed to have no effect on the participants who take it. All participants, regardless of group, are required to receive their respective tominersen treatment or placebo the same amount of times. This is also a double-blind study, meaning neither the participants nor the researchers are aware of who is receiving the treatment, or who is in the experimental group.

Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Researchers focused on recruiting patients demonstrating symptoms of the manifest stage of HD based results from previous studies, and the ability to measure these symptoms as indications of improvement or not.

Key inclusion criteria required in order to have qualified for enrollment in 2019 include:

1.A clinical diagnosis of manifest HD (defined as a DCL score of 4)

The Huntington Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS) diagnostic confidence level (DCL) is the standard measure used for clinical diagnosis in at-risk individuals and is based solely on the motor evaluation [ref]Biglan, K. M., Zhang, Y., Long, J. D., Geschwind, M., Kang, G. A., Killoran, A., Lu, W., McCusker, E., Mills, J. A., Raymond, L. A., Testa, C., Wojcieszek, J., & Paulsen, J. S. (2013). Refining the diagnosis of huntington disease: The PREDICT-HD study. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 5(APR). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2013.00012 [ref/]. The DCL ranges from 0 to 4, where a patient who is unimpaired would qualify for a DCL score of 0, while a patient with motor impairments that are unequivocal signs of HD would qualify for a DCL score of 4. When tracking HD’s impact of motor function, the first diagnosis of a DCL score of 1 represents the onset of motor impairments, and that of 4 indicates the onset of HD diagnosis [ref]Liu, D., Long, J. D., Zhang, Y., Raymond, L. A., Marder, K., Rosser, A., McCusker, E. A., Mills, J. A., & Paulsen, J. S. (2015). Motor onset and diagnosis in Huntington disease using the diagnostic confidence level. Journal of Neurology, 262(12), 2691–2698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-015-7900-7[ref/].

2.Be between the ages 25-65 years

3.Genetically confirmed disease by direct DNA testing with a CAP score >400

A CAP score [ref] Update on Huntington’s Program and Clinical Trials from Roche/Genentech – YouTube. (n.d.). Retrieved January 21, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gAi6X5-Z2xo [ref/] measures how long an individual has lived with their mutation burden. The formula to calculate this score is:

CAP score = [Age in the years at study start] x [CAG – 33.66]

It has been shown in studies that variability in CAP scores results in different patterns of progression overtime on key clinical outcomes, such as the DCL or the total functional capacity score. Because of this, by using an objective CAP score criteria, the researchers can make sure that the trial’s participants will have a certain sensitivity to changes resulting from the treatment, should there be any change, and will allow these changes to be measurable.

4.Independence scale >= 70:

This scale is intended to clinically evaluate a candidate’s baseline functional status, given that the trial will be a 25 month intervention period. An independence scale score of 70 or higher thus means that a candidate is able to maintain self-care and core activities of daily living (ADLs). This not only allows the researchers to confirm that the candidate is able to functionally participate in the study for the length of the study period, but further confirm that the candidate is someone who would benefit from this treatment, and allows these benefits to be measurable.

5.Be ambulatory (able to walk) and verbal

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria for qualifying for the study included having any active serious medical condition, clinically significant laboratory, or vital sign abnormally during screening that, in the investigator’s judgment, precluded the patient’s safe participation in and completion of the study. Additionally, candidates who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or intended to become pregnant during the study or within 5 months after the final treatment dose did not qualify to participate.

The estimated completion date of the study is July 9, 2022.

More

Part of the lived experience of being at risk for or living with Huntington’s disease (HD) is thinking about the unique challenges involved with planning a family. Although the possibility of HD being inherited can make the decision of having a baby very difficult, various options have been developed for people living with hereditary diseases to reduce this risk. One such option is in vitro fertilization (IVF) with preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). IVF is an assisted fertility medical procedure where a donor egg is fertilized by the donor sperm outside of the body, and implanted into the uterus. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) is a form of prenatal diagnosis applied to potential parents who are potential or known carriers of a genetic disease, such as Huntington disease. This procedure was developed to address the desire for people with, or at risk for, HD to know if they could have children without passing the disease on to the next generation. Since the birth of the first “IVF baby” in 1978, more than four million IVF babies have been born worldwide .

What is in vitro fertilization (IVF)?

The term “In vitro” means “performed or taking place in a test tube, culture dish, or elsewhere outside a living organism” . In vitro is often used to describe studies and procedures performed outside the body and in a glass laboratory dish or container. In vitro fertilization (IVF) is an assisted fertility technique involving a series of procedures performed to combine a man’s sperm and a woman’s eggs outside the woman’s body, and ultimately implant a fertilized egg (an embryo) into the woman’s uterus . The IVF process involves the following steps:

1. Ovarian stimulation

This involves the prospective mother taking a series of medications to release more eggs than normal. The IVF cycle (a term commonly used to describe the steps involved until implantation) begins with the mother taking fertility drugs for a span of 8 and 12 days . Fertility drugs work by triggering the release of hormones that regulate ovulation. Depending on the patient, a prospective mother’s doctor may recommend starting an IVF cycle by taking birth control for a number of days to prevent ovulation from happening too early in the cycle. After their fertility medication, the prospective mother is administered a a “trigger injection” of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), lupron , or both to stimulate their ovaries to produce eggs . Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) is a hormone released during pregnancy that stimulates the production of other hormones that helps maintain the uterus for pregnancy . Lupron is a drug containing synthetically made gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog/agonist (GnRH) intended to shut down the ovaries; then other drugs are used to stimulate egg production and facilitate multiple egg extraction.

2. Egg retrieval

36 hours after the trigger injection, the eggs are removed from the body through an egg removal technique, the most common being a transvaginal ultrasound aspiration . During this procedure, the prospective mother is first sedated and given pain medication. An “ultrasound probe”, which looks like a long probe with a needle at the tip, is inserted into the vagina, and the needle guide through the vaginal wall and into the follicles. Once the needle is inside a follicle, the eggs are suctioned into the needle’s canal . Multiple eggs can be removed in a span of about 20 minutes; an average of 10-15 eggs are retrieved during the process . The retrieved eggs are then placed in a nutritive liquid known as “culture medium” and incubated for .

3. Sperm retrieval

Sperm can be derived from a semen sample (from a partner or sperm donor) at a lab or a clinic the morning of egg retrieval. Other methods, such as testicular aspiration, which involves the use of a needle or surgical procedure to extract sperm directly from the testicle, could be recommended by a health professional under certain circumstances .

4. Fertilization

Fertilization can be attempted using two common methods. One is conventional insemination, which involves healthy sperm and mature eggs being mixed in a dish and and incubated overnight . The other is intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), where a single healthy sperm is injected directly into each mature egg. ICSI is often used when semen quality or number is a problem or if fertilization attempts during prior IVF cycles failed .

5. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD)

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) is a form of prenatal diagnosis recommended to potential parents with known carrier status of a genetic disease, such as HD . PGD allows a prospective parent to check if a fertilized egg carries the disease causing gene, even before implantation. During this process, 5-6 days after fertilization , the embryo is grown in the laboratory until it has divided to about eight cells; this takes about two to three days. One or two cells are removed from each embryo at this stage to undergo genetic tests for HD. The removal of these cells at this early stage of development does not affect the embryo’s development. After testing, the HD-negative embryos are implanted into the prospective woman’s womb. When choosing to pursue PGD, there is a “non-disclosure PGD” option that enables an at-risk parent to have HD-free children without finding out their own genetic status. Specifically, at-risk parents remain blind to their own results, the embryo’s genetic test results, how many successful fertilizations occurred, and how many embryos are implanted. Only the health professionals handling the genetic tests of the embryos are aware of the results. If there are no mutation-free embryos, the IVF cycle stops here, and the parents are informed that the process was unsuccessful without being informed specifically why . Some risks associated with this test include embryos being damaged when cells are removed, and the HD test being inconclusive due to a lack of DNA. This could result in a healthy embryo outside of the body without an official genetic diagnosis (if they are positive or negative for the genetic disease).

6. Embryo transfer

If PGD is performed, 5-6 days after fertilization, one to two healthy embryos found not to be carriers of HD are selected to be transfered. If PGD is not performed, a “fresh embryo transfer” is typically performed, where 1-2 days after fertilization, one to two healthy embryos are chosen to be transferred. During the embryo transfer procedure, the health professional will insert a long, thin, and flexible tube called a catheter into the prospective mother’s vagina. After numbing medication is applied to the cervix, the tube is guided through the cervix and into the uterus, where one or more embryos are placed using a syringe attached to the catheter; if successful, an embryo will implant in the lining of your uterus . The mother may be instructed to receive a progesterone supplementation (administered via injection and vaginal suppositories) to maintain a thickened uterine lining .

7. Pregnancy Testing

About 12 days to two weeks after egg retrieval, a health professional will test a sample of the mother’s blood to detect whether they are pregnant. At least two pregnancy tests are typically done following the embryo transfer.

Many options are available to people at risk for HD, or who have been diagnosed with HD, who wish to start a family. One of these options includes IVF with PGD. If a prospective parent is at risk but has not received a genetic test, embryonic genetic testing such as non-disclosure PGD can be performed while protecting the at-risk parent from learning of their gene status . Research on this topic continues to be underway to reduce the risks associated with the process, and improve the success of the process .

The HOPES podcast team is currently working on a podcast focused on the personal experiences of people who have undergone IVF because of their relationship with HD. Stay tuned for its release!

More

Recent research has focused on tackling the issue of the unmet medical need of an objective and quantitative biomarker for Huntington’s disease (HD). The discovery of biomarkers specific to the different stages of HD could help physicians monitor the physical changes of an individual’s HD during asymptomatic stages, and help improve the quality of treatment at all stages by allowing a better measurable assessment of an individual’s HD.

What are biomarkers?

Molecular, histologic, radiographic, or physiologic characteristics of a disease are all types of biomarkers. The FDA defines a biomarker as a “characteristic that is measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an intervention”. Biomarkers come in difference forms, and can serve various purposes in disease research. Clinically, for example, a biomarker can be used as a measurable indicator of the severity or presence of a disease state, or the effects of a treatment.

If you have ever gone to the doctor, it is likely that you have been asked to take an x-ray, or receive a blood or saliva test. Each one of these tests and x-rays is looking for a specific biomarker, an indicator of the state of the body that helps doctors predict an individual’s risk of a specific disease. For example, if you come into a doctor’s office with a sore throat, they might take a swab sample from your throat in order to test for the presence of Streptococcus pyogene, the bacteria that causes strep throat, in order to diagnose you with strep throat. In this scenario, the bacteria is the biomarker . In the future, you could be tested again for the presence of this biomarker to evaluate if the strep throat is gone, or is still present.

Scientists have taken a huge interest in biomarkers because of this powerful ability to give insight into the state of the human body. One such scientist is Dr. Joshua Chiappelli at the University of Maryland. In a research study, Dr. Chiappelli collected hundreds of saliva samples, and tested them in hopes of finding a biomarker specific to schizophrenia. Through his research, he found that elevated levels of a type of molecule called “Kynurenic acid” in saliva at any age could be an indicator of an individual’s risk to a specific type of schizophrenia . Similar studies like this are currently underway in hopes of finding biomarkers specific to the progressive stages of HD.

Biomarker research and HD

The goal of many HD biomarker studies is to find ideal biomarkers that are closely linked and specific to the state of someone’s HD. Because of its progressive nature, there are no defined stages for HD; however, researchers and physicians often use this categorization of symptoms to better describe the progression of HD. For example, the period in which no motor signs are present is commonly referred to as the “premanifest phase”. This means that at this stage, an individual’s risks for the disease cannot be detected using existing neurological assessments. Currently, some of the clinical diagnosis and progress evaluations of HD rely on a neurological assessment of motor and cognitive ability, such as chorea or psychological symptoms, and blood tests for the presence of CAG repeats . Although these current methods open the possibility for preparedness and planning ahead with disease-modifying treatments, there is a pertinent need for more reliable biomarkers that measure “disease activity”, as well as biomarkers that help in evaluating the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. Recent research studies have pursued this need through investigating the ongoing cellular processes of HD, with hopes of better understanding the state and conditions of the body at the microscopic level before and after the onset of HD symptoms. Ultimately, scientists hope to discover a “premanifest phase biomarker” which would ideally help in monitoring changes in asymptomatic individuals. Biomarkers such as this could also help in providing an objective measurement when assessing the progression and severity of a patient’s HD, which could contribute to the improvement and appropriateness of clinical care.

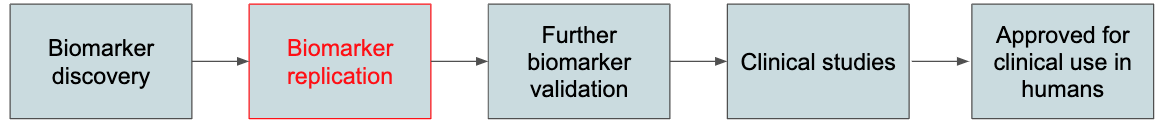

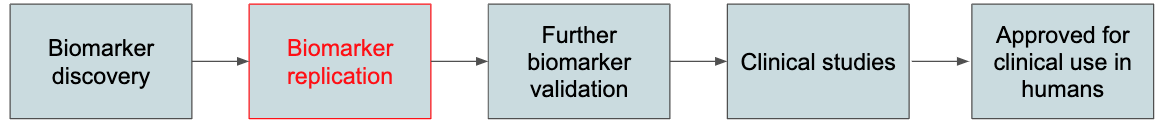

Biomarker research is extensive, and requires multiple steps after a biomarker is discovered to reach the point of clinical adoption and approved use in patients. Figure 1 displays the step by step phases of biomarker development. Thus far, many of the biomarker discoveries made for HD have been unable to surpass the second step (highlighted in red in Figure 1). This is due to variability between research studies that aim to replicate the results of the discovered biomarker, which cause conflicting results.

Figure 1 . Phases of biomarker development

“Wet Biomarker” research for HD

To address this issue, Professors Edina Silajdzi and Maria Bjorkqvist published an article in the Journal of Huntington’s Disease, in which they evaluate almost all studies done on “wet biomarkers” . They defined a wet biomarker as a potential biomarker that is objectively measured in a bodily fluid, such as blood, urine, saliva, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In addition to reviewing wet biomarker research studies, the authors make detailed recommendations for improving biomarker research for HD. Specifically, they pinpoint biological variation, study design, patient selection, and even time at which an experimental sample was taken as potential considerations for improvement. The studies they reviewed, along with their findings, are described below.

Immune markers

The immune system has been previously suggested to play a role in HD progression . Specifically, a number of studies have highlighted the existence of an immune response in HD patients. In one study, scientists at King’s College London performed an extensive screen of HD patient plasma and identified elevated levels of a specific immune system protein in HD patients .

The authors hypothesised that a specific immune protein called “proinflammatory cytokine IL-6,” or IL-6, induces the release of proteins that increase or decrease in concentration in response to inflammation. These proteins further trigger a cascade by activating other immune proteins and factors responsible for cleaning up any dead cells in the body. A follow-up study demonstrated that IL-6 was elevated in HD subjects, even during the premanifest phase of HD. Thus, the study proposed the possibility of immune proteins, specifically inflammatory proteins such as IL-6, in plasma being potential biomarkers for HD progression tracking. However, no other study has been successful in replicating these results, which has prevented scientists from arriving at a consensus that this is a biomarker for HD

Another group of studies focused on investigating a liver protein called C-reactive protein (CRP), which normally rises when there is inflammation in your body, as a potential biomarker in HD. One study found decreased levels of CRP in one HD subject group , while several other studies reported increased CRP levels in HD subjects . The scientists of this study explained that one potential explanation for increased CRP levels is an inflammatory response in HD patients caused by mutant huntingtin expression. However, antipsychotics, a type of medication to control psychotic symptoms often taken by HD patients, were also described to instigate an inflammatory response; thus, this study expressed the possibility of this CRP increase being reflective of the antipsychotic use by the HD subjects they studied , further adding to discrepancies in CRP biomarker research.

Metabolic markers

Research shows that there is a “negative energy balance” in HD patients, which means that their energy expenditure typically exceeds their caloric intake . This metabolic factor contributes to the peripheral manifestations of HD, such as weight loss and muscle wasting. Because of HD’s impact on the body’s metabolism, many researchers have focused on testing “metabolites”— proteins or molecules involved in metabolism — as potential biomarkers for HD. One study analysed the serum, the fluid that remains when proteins involved in blood clotting are removed, from control subjects and premanifest and early stage HD subjects . The study found that changes in amino acid metabolism occur even before the onset of symptoms. Other studies that have focused on the levels of amino acids in HD patients consistently reported these changes to be correlated with weight loss, disease progression and abnormal triplet repeat expansion; however, conflicting results were received .

Further metabolic research has aimed at investigating different protein markers of metabolism in HD, such as those involved in cholesterol metabolism . Cholesterol is a waxy, fat-like substance that’s found in all the cells of the body, and is needed to make hormones, vitamin D, and important substances involved in food digestion . Although no significant changes were demonstrated in peripheral levels of total cholesterol, a specific brain cholesterol metabolite called “ – 24(S) hydroxycholesterol,”- or 24OHC, was consistently observed to be reduced in the plasma of individuals with HD . Reduced levels of cholesterol precursors (the inactive form of a protein that can be turned into an active form) called lanosterol and lathosterol and a bile acid precursor (a type of cholesterol involved in fat digestion) called “27-hydroxycholesterol” were also demonstrated . However, one of the suggestions made for further validation of this is to follow subjects longitudinally, or long-term, to examine the rate of change of metabolic markers as the disease progresses .

Novel biomarker discoveries

An Oculomotor Biomarker

Figure 2. Experiment outline

A 2020 study published in the Journal of Neurology took a different approach at identifying potential HD biomarkers . In hopes of addressing the lack of a quantitative and reliable way to clinically diagnose HD, a group of scientists focused on the potential for the altered eye movements in HD patients to be physical motor biomarkers of HD. Thus, they performed an eye-movement analysis to develop a novel eye-movement based model to diagnose and monitor the progression of (HD).

The study evaluated the eye movement in 25 participants, 10 of whom were early symptomatic for HD, 10 were in the premanifest phase for HD, and 5 were healthy controls. The research group developed machine learning algorithms for disease state classification to create an algorithm able to predict and differentiate HD patients from healthy individuals with high accuracy. These algorithms were able to differentiate HD patients from healthy individuals with high accuracy. Overall, the study demonstrated the feasibility of considering quantitative eye-movement assessments as objective biomarkers for HD that could serve as a support tool in medical decisions and therapeutic development.

Neurofilament Light protein as a Biomarker

In 2017, a study investigated whether neurofilament light protein NfL (also known as NF-L) in blood is a potential prognostic marker of neurodegeneration in patients with Huntington’s disease . NF-L is the smallest of three subunits that make up neurofilaments, which are major components of the neuronal cytoskeleton; NF-L is released from neurons when they become damages . In individuals with HD, four small-scale cross-sectional studies found raised concentrations of NF-L in their cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the clear body fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord . In the 2017 study, plasma samples from 97 control patients and 201 individuals at risk for HD were analyzed. In 104 individuals with premanifest HD, NF-L concentration in their plasma was associated with subsequent clinical onset during a 3-year follow-up period. Thus, this study proposed that concentrations of NF-L in CSF and plasma were correlated in HD mutation carriers. NF- L in plasma thus shows promise as another potential prognostic blood biomarker of disease onset and progression in HD.

Future directions

Although HD biofluid marker literature shows no clinically validated biomarkers for HD, much progress has been made in better understanding what improvements need to be made to promote wet biomarker discovery. Every research study reveals a lesson learned for the next, as they provide guidelines that benefit future biomarker studies in HD. The development of a reliable biomarker would provide a more objective and quantitative measuring tool for HD compared to clinically based methods currently used in HD trials. Additionally, further pursuing biomarker research will aid in the development of therapies for HD by providing a more accurate and specific means of evaluation. Taken together, this biomarker research analysis offers new potential avenues of biomarker research for HD, and serves as a useful tool source of insight for future biomarker researchers.

More

Studies have found that unhealthy lifestyles are a major factor in the development and worsening of many chronic diseases . However, immersive retreat experiences have been shown to have various health benefits, beginning from immediately after, to five-years post-retreat . Retreats, specifically youth retreats, are often a time and place for intentional bonding within a group. They are purposeful, meaning they strive to teach participants a certain skill set, build community, and/or are a place for growth through individual and group activities, reflections, and time away from each participant’s everyday life. HD youth retreats are unique in that they allow youth with HD to meet others living similar experiences, allow them to build a strong support network, and are planned to provide ample resources for all youth impacted by HD to make the experience accessible. Below are a few examples of HD- specific youth retreats that fulfill this goal.

The North American HD Youth Camp

The annual North American HD Youth Camp hosted by the Huntington’s Disease Youth Organization (HDYO) offers young individuals affected by HD a chance to meet other youth in the same shoes. Throughout the course of the camp, these individuals share experiences, grow more aware of HD through educational workshops, share experiences, and participate in various activities, such as swimming, rock climbing, hiking, and archery. Through these activities, the creators of the camp hope to diminish feelings of isolation among HD youth, and build strong peer connections with others in experiencing similar situations.

The camp is open to Young people ages 15-23 that live in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico who are impacted by HD, and is capped at a capacity of 45 participants. The entirety of the camp is hosted by Camp Cedar Glen (located in Julian, CA about an hour from San Diego, CA) in mid-August for 5 days, and is free to attend for all participants (camp, food, and travel costs are covered).

The camp is run by staff from HDYO (here is a full list of all staff), HD professionals (social workers and genetic counsellors) from around the country, and a trained and trusted group of young adult volunteers from the HD community in North America to form the support team. Additionally, all camp activities are supervised by certified staff that are employees of Camp Cedar Glen. On a daily basis, the days will start with breakfast as a group. After that, depending on the day, there will be a mix of recreational activities, educational sessions and some sharing sessions. There is no religious aspect to the HDYO camp, despite Camp Cedar Glen hosting its own summer camp with a religious component (unrelated to HDYO). Overall, the aim of the camp is for young people to feel more supported, develop an improved understanding of HD, and form strong connections. You can find an article detailing the experiences of past participants and staff here.

National Youth Alliance (NYA) Youth Retreats

The Huntington’s Disease Society of America’s National Youth Alliance (NYA) aims to motivate youth to get involved in their local HDSA Chapters, affiliates, and support groups through education, fundraising, advocacy and awareness events for Huntington’s disease. The NYA is a collection of children, teens and young adults from across the country whose mission is to “not only support young people within the HD community, but also inspire the youth of HDSA to get involved in the battle against HD and be proactive in this fight”. The NYE hosts Youth retreats in various cities across the United States to foster learning and community building among young people ages 12-29 whose lives are touched by Huntington’s disease. The retreat includes professionally led talks about issues relevant to young people affected by HD, camp activities, and a group art project to conclude the day. This past year, the retreats were located in Pittsburgh, Chicago, New Orleans, and Sacramento.

The event is free to attend for all participants; it includes a transportation reimbursement of up to $350 for attendees (although reimbursement rates vary depending on accessibility), and hotel rooms reserved for youth and their parents who have to travel to attend their retreat. If a participant is currently receiving any medical treatment, or taking medications, they are required to fill out a medication information sheet. Additionally, the attended or their parent/guardian is responsible for their individualized medical care while attending the event. More logistical information can be found within the registration portal that opens every year for the retrats.

Other Program Resources

The Huntington’s Disease Society of America also has a website page that allows you to find events happening in your area upon providing a zip code. These events range anywhere from family retreats to team walks to conferences!

More

By Maria Suarez-Nieto and Sepehr Asgari

On the 2nd of November, 2019, the Stanford University School of Medicine’s Huntington’s Disease Center of Excellence held their inaugural Stanford Huntington’s Disease Patient Care Symposium. Hosted in Mountain View, California, the event saw the participation of HD patients, caretakers, healthcare professionals, students, and members of the broader HD community. The symposium highlighted the latest advances in HD research from multiple perspectives, providing those in attendance with valuable new information.

The morning started with Daniel Jarosz, PhD and Assistant Professor of Chemical and Systems Biology and Developmental Biology at Stanford University, who dreams of the day when a treatment for HD exists. His informational talk focused on highlighting breakthroughs in basic science research for HD and other neurodegenerative diseases. Dr. Jarosz opened by explaining the work of Judith Frydman, who found that a chaperone protein, a type of protein that assists other proteins in carrying out their function, called TriC binds to the ends of Huntingtin protein fibers. This prevents the Huntingtin protein from aggregating, thereby suppressing the toxic effects of Huntingtin aggregation. Scientists further found that treating Hungtintin rich neurons with TriC helped normalize the structure of the protein. After explaining the methods used to discover that Huntingtin aggregates spreads between cells, Dr. Jarosz shifted his focus to explain how he used novel African turquoise killifish as a model for HD. Using that model, he identified that aged individuals have a strong enrichment in prion-like character among proteins known to form aggregates, meaning that aggregated proteins can spread similar to how prions do. If these findings are further confirmed, Dr. Jarosz stressed how this could be a new aspect of neurodegenerative disease behavior that we could potentially target.

Afterwards, Sharon Sha, MD, MS, Clinical Associate Professor of Neurology and Neurological Sciences at Stanford University and Co-Director of the Huntington’s Disease Center of Excellence and Ataxia Clinic, gave her talk on “Cognitive challenges in HD and ways to work around them.” Sha opened with an overview of symptoms commonly found in HD patients, which allowed her to introduce the main topic of her talk, cognitive symptoms. She deemed the cognitive impacts of HD “underrecognized,” and continued with explaining how these symptoms manifest in individuals, primarily by affecting their executive function, which could impact individuals years before motor impairments. Her research found that premanifest HD patients (patients in which symptoms have yet to arise) were more aware of presenting executive function problems than early stage HD. Sha proceeded to shift her focus to describing strategies that help treat cognitive problems, along with those that do not; she recommended using memory aids, decreasing multitasking, and being receptive to help. She continued by explaining that Donepezil, a drug commonly used to treat dementia in Alzheimer’s disease, does not work effectively to treat cognitive problems, along with the potential for another drug called Rivastigmine, and closed with addressed the prevalent insurance issues associated with clinical trials.

The third talk was given by John Barry, MD and professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford Medical Center, on the neuropsychiatric challenges that HD patients face. He opened with explaining how unawareness is hard-wired, not solely deniel. Barry described the disabling psychiatric symptoms often seen in HD patients, such as apathy, denial, depression, irritability, and anger among others; he emphasized that the disease, rather than the individual themselves, is the cause for these symptoms,.

After a short break, the morning resumed with a moving patient testimonial from Sheila A. She spoke about her own experience being diagnosed, and touched upon the guilt she felt at knowing it is possible that she passed HD down to her children, who were already born when it was discovered that HD is in her family. She explained the lack of resources available to her and her family living in Scotland at the time, along with her experience of her father being misdiagnosed. Sheila continued with her experiences in enrolling and participating in clinical trials that drove her to the US; despite not knowing what treatment group she belongs to, she is hopeful for the future of HD research and treatment, ending on the note that she finally felt “dignified in a really undignified disease”.

Following Sheila’s testimony was Kristina Cotter, PhD, who presented her dissertation research on “Positive attitudes and therapeutic misconception around clinical trials in the Huntington’s disease community.” Using a PACT-22 scale, which is a commonly used metric for clinical trial attitudes, her team developed a survey with two measures to assess clinical trial attitudes and understanding in the HD community. After distributing the survey via emails, flyers, and social media through HD-related organizations and evaluating 73 responses, Cotter and her team found that respondents viewed clinical trials positively and generally viewed trials as safe. She also explained that individuals with prior HD-related research experience were less likely to have negative expectations about trials than those without research experience, and that level of invasiveness was negatively correlated with willingness of an individual to participate. Interestingly, Cotter mentioned how she did not expect to find that individuals with HD were more likely than the other groups to experience therapeutic misconception; she concluded with recommending to use her findings to strengthen informed consent during HD clinical trial recruitment.

The last talk of the morning was a concise yet information-packed update on ongoing HD clinical trials by Brent Bluett, DO, clinical assistant professor in Neurology and the Neurological Sciences and Marcus Parrish, PhD of the Department of Chemical and Systems Biology. He touched briefly on a variety of ongoing drug-related clinical trials, shared contact information for audience members interested in such trials, and described how AMT-130 gene therapy has been found to lower huntingtin protein and improve HD symptoms in animal models. Bluett continued with emphasizing the ability to use of biomarkers as indicators of the severity and/or presence of HD, and concluded that biomarkers could be clinical trial endpoints for the HD community.

The afternoon began with an educational overview of nutrition, given by, Veronica Santini, MD, MA, and co-director of the Huntington’s Disease and Ataxia Clinic. She explained the higher total energy required for those with HD due to higher movement. She continued to explain healthy and unhealthy recommendations for HD patients; specifically, she mentioned decreasing lactose intake, while increasing the “colors” on a plate, particularly through vegetables.

The afternoon continued with a panel discussion about “Support Challenges in Huntington’s Disease” with social workers from the local community. Moderated by Dr. Sha and Dr. Santini, the panel consisted of Andrea Kahn, MS, CGC, Amee Jaiswal, LCSW, and Betsy Conlan, LCSW of Stanford Health care, among others. Each of these panelists introduced themselves gave attendees the opportunity to ask any questions they may have. They each provided expert answers for all questions from the audience members, which included those on along the topic of insurance protections, trust planning, pre-existing conditions under the Affordable Care Act, and long-term care. Panelists also recommended HD patients and families to enroll in a long term insurance plan prior to getting tested, mentioning the impact which positive results can have on the resources and coverage of an insurance plan.

The event concluded with a talk by Kristin Morris, PT, DPT, NCS, and physical therapist from the Stanford Neuroscience Health Center. She demonstrated examples of physical therapy style movements for those impacted by HD, and offered the opportunity for attendees to join in trying them out.

The first annual iteration of Stanford Patient Care and Research Symposium was a great success, bringing valuable information to and bringing together the HD community.

More